Case for investment: Nutrition

Overview

- Just one small boiled orange-fleshed sweetpotato can provide the daily vitamin A requirement for a young child, reducing the risk of infection, stunting or blindness.

- Potato, a staple food in many developing countries, is a good source of zinc, iron, potassium, and vitamin C.

- CIP breeders have developed biofortified zinc- and iron-rich potato varieties.

- The International Potato Center (CIP) has reached 6.5 million households with biofortified orange-fleshed sweetpotato to improve vitamin A intake.

- Evidence shows an integrated seed distribution and nutrition education approach is effective in improving diets of families at risk of malnutrition.

- CIP aims to reach 10 million households in the next five years with nutritious potato and sweetpotato varieties to improve diets.

- Investment priorities include:

- breeding climate-resilient, consumer-accepted, biofortified potato and sweetpotato varieties, including varieties with multiple essential nutrients;

- inclusive seed system development to disseminate new varieties;

- gender-responsive nutrition education and behavioural change programs; and

- diversification of inclusive and equitable value chains to expand cultivation and access to nutritious foods in urban markets.

Introduction

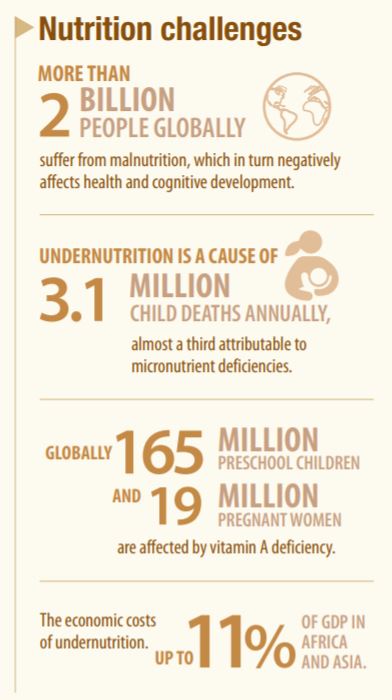

Malnutrition presents an urgent development challenge. Zinc, iron and vitamin A deficiencies—essential for healthy growth and development—are among the most debilitating forms of undernutrition, and they disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, including women of childbearing age.

Potatoes and sweetpotatoes can provide important sources of these essential nutrients. Potato is a good source of zinc, iron, protein, potassium and vitamins C and B6, making an important contribution to diets in regions where resource-poor populations have limited access to other foods. Just 100g of boiled, unpeeled potato can provide up to 16% of the recommended daily intake of potassium and 30% of recommended vitamin C intake. Benefits like these are especially important in mountain regions of rural Africa and Latin America, where people eat 300–800g of boiled potatoes a day, accounting for almost 40% of their energy requirements.

While iron concentration in cooked potatoes is lower than in cereals and legumes, its bioavailability—the amount of iron available for use by the body—is proportionally higher than in wheat and beans, in part because vitamin C facilitates iron absorption.

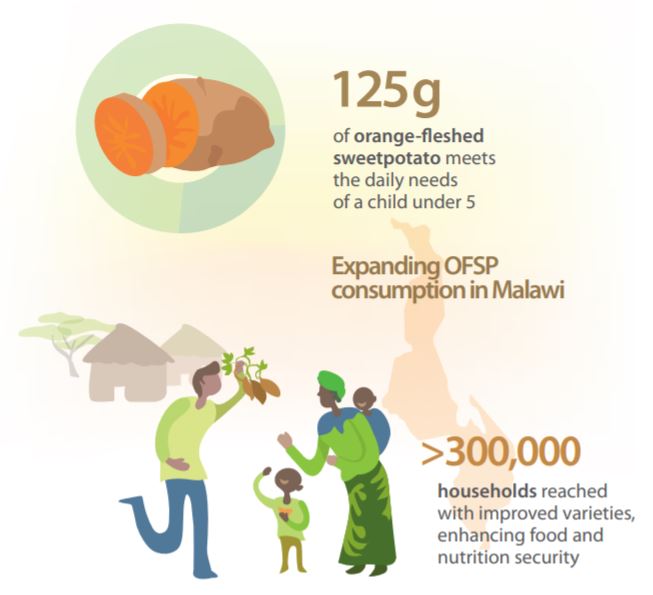

Orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP) contains high levels of beta-carotene, which is converted by the body into vitamin A. Just 125g of boiled OFSP can provide the recommended daily allowance of vitamin A for children and women who are not breastfeeding. In addition, OFSP contributes significant amounts of vitamins C, E and several B vitamins, as well as dietary fiber, iron and magnesium. Purple-fleshed varieties, on the other hand, are rich sources of antioxidants. Sweetpotato leaves are also rich in vitamins, beta-carotene, and functional compounds including protein, amino acids and complex carbohydrates.

Potatoes and sweetpotatoes offer cost-effective and sustainable opportunities to supplement diets. Even at low yield levels, a family of five can grow enough OFSP on a 500m2 plot to meet their vitamin A needs, while potatoes contain more protein per unit growing area than alternative staple crops.

Early-maturing improved varieties with elevated levels of essential nutrients can produce nutritious food before rice or wheat are ready for harvest. They can contribute to the diversified diets needed to address “hidden hunger”—a diet sufficient in quantity but lacking in essential micronutrients.

Crop breeders have prioritized the development of more nutritious, climate-resilient potato and sweetpotato varieties with the qualities desired by local growers and consumers—but this is not enough to encourage successful adoption by farmers. Farmers seek varieties that are pest-resistant and drought and heat tolerant, while consumers look at factors such as taste and texture. To meet these demands, CIP collaborates with businesses, model farmers and national agricultural research systems to establish seed systems that guarantee the availability of quality planting materials to farming households.

Building blocks

Breeding

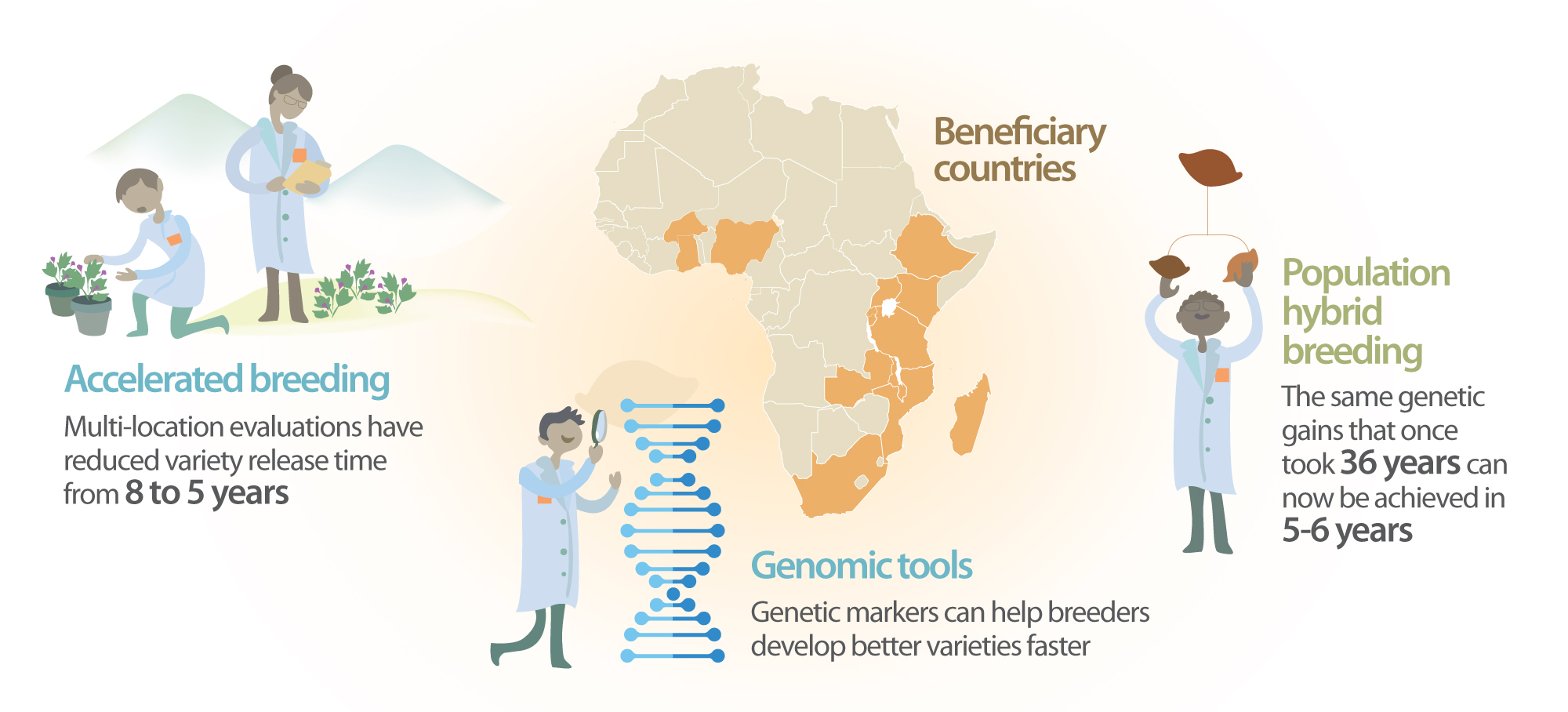

Over the past 15 years CIP has cut the time needed for developing and releasing new sweetpotato varieties using conventional breeding from eight years to four or five, and new biofortified varieties have been released in at least 22 countries. Progress is also being made towards the goal of producing zinc- and iron-rich sweetpotato, which would be the first biofortified crop to deliver three essential nutrients.

Biofortification increases vitamin and mineral uptake

Substantial evidence supports the benefits of biofortified orange-fleshed sweetpotato—the result of a breeding process designed to enhance the density of minerals and vitamins. This is crucial for areas like sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia where more than 40% of children under five suffer from vitamin A deficiency. A study in Mozambique in 2002-04 demonstrated that increased OFSP consumption by children reduced vitamin A deficiency by 15%. Since then, CIP has contributed to the breeding and release of more than 150 OFSP varieties in sub-Saharan Africa alone. A subsequent study in Kenya in 2017 also indicated that nutrition education and increased consumption of OFSP contributed to improvements in the vitamin A status of pregnant and lactating women. It is estimated that replacing white- with orange-fleshed sweetpotato could reduce the burden of vitamin A deficiency by up to 22% in the 17 African countries where the crop is widely grown.

Potato breeding research is taking advantage of the crop’s ability to deliver nutrients to the human body. Over a decade of conventional breeding has resulted in potato clones with 40–80% more iron and zinc than cultivated varieties. Varietal selection is taking place on three continents and preliminary findings from bioavailability studies in Peru indicate that the iron from biofortified potatoes is absorbed at a much higher rate (29%) than that from other biofortified crops such as beans (3–5%) and pearl millet (7–10%). Given consumption levels in the Andean mountains, it is expected that these potatoes would meet more than 50% of the average requirements for iron among women and up to 28% for children.

Farmer adoption/ behavioral change

Two decades ago, few Africans grew OFSP as it was considered as poor people’s food. Today, education and awareness campaigns about the nutritional qualities of OFSP have successfully contributed to their increased production and consumption. In a 10-month pilot initiative in Kenya, community health workers provided nutrition advice to new and expectant mothers along with vouchers for OFSP planting material. When CIP researchers returned to the area a year later, 75% of the families who received both the nutrition advice and OFSP vouchers were growing those new varieties. Embedding nutrition education into interventions and enhancing access to OFSP varieties proved effective. Promotional activities through public health services have improved maternal health-seeking behavior, nutrition knowledge, dietary vitamin A intakes, and vitamin A levels.

Scaling up sweetpotato through agriculture and nutrition

A six-year GBP 18.4 million project, launched in 2013 by CIP and 20 partners, used a two-pronged approach in providing farming families with OFSP planting material and nutrition education on the benefits of the crop. The project reached more than 2.3 million households with children under five across Bangladesh, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Tanzania. As a result, approximately 1.3 million women and children regularly ate OFSP, when available, putting them at lower risk of vitamin A deficiency and its health consequences.

Market development

Successful market development has played an important role in expanding consumption of pro-vitamin-A sweetpotato in Africa. CIP scientists developed and disseminated a method to produce vacuum-packed sweetpotato puree – with a shelf life of three-to-six months–that can be used to make varied baked or fried products. The puree can be substituted for 45 percent of the wheat flour in bread, reducing production costs and resulting in a more nutritious product. The sale of sweetpotato bread in various African countries has increased the amount of vitamin A in consumers’ diets, spawned new value chains from farmers to retailers, and created income opportunities for women and young people.

Sweetpotato bread takes off in Kenya

The production of shelf-stable, orange-fleshed sweetpotato puree by two Kenyan companies has enabled large bakeries to sell nutritious sweetpotato bread and other products, since they now have a year-round supply of that ingredient. Kenya’s two largest supermarket chains, Tuskys and Naivas, sell thousands of loaves of sweetpotato bread and buns each day at dozens of stores. They charge slightly more for the sweetpotato breads, annual sales of which are about USD 1 million. Two slices provide about 10% of the daily vitamin A requirement of an adult, whereas growing demand for orange-fleshed sweetpotatoes by puree producers is motivating more farming families to grow and eat the crop.