Late blight is the most destructive potato disease in the world. It affects all potato producers (small-scale, commercial, seed producers, even urban producers) and the annual losses in developing countries are estimated at EUR 10 billion. Late blight can attack many varieties of potatoes and most farmers use large quantities of fungicides to control this disease. The fungicides can cause environmental damage as well as human health problems when they are misused, since many farmers do not use protective gear that would prevent contact with this type of pesticide. So any technology that optimizes fungicide use to control late blight represents significant progress for potato producers.

Toward this end, the International Potato Center (CIP), in partnership with research and development institutions in Ecuador and Peru, has developed a low-tech tool to help farmers optimize fungicide use. Development of the tool was based on three questions farmers need to answer when they are considering using fungicides:

- When do I start to apply the fungicide?

- Which fungicide should I use?

- How often should I apply it?

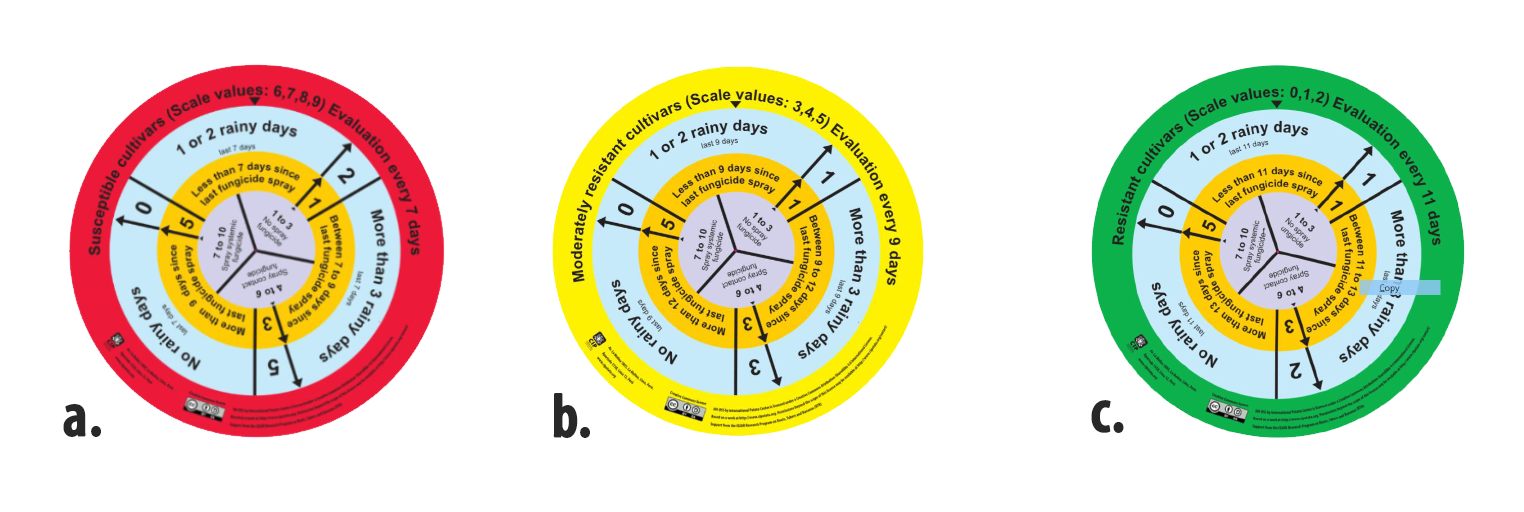

The CIP tool is called disc tool for potato late blight management. Unlike the systems used in developed countries, the CIP tool is printed on cardboard and does not need the Internet or batteries. Yet it enables integration of the most important factors in the decision on whether to use fungicides: How resistant is the potato variety of concern? Number of days of rain in last week? Number of days since last fungicide application? Taking these three factors into consideration, the tool helps farmers decide when to initiate fungicide application, which fungicide to use, and how often to apply it.

Evidence of the disc tool’s effectiveness has grown over the last five years in 11 field experiments in Peru and Ecuador. In addition, a study was conducted in Carchi (Ecuador) in which 150 farmers received training in how to apply these tools and their results were compared with management by another 150 farmers in the same zone. On completion of the study, the successful results were clear. The farmers who followed the disc tools’ recommendations used less fungicides, had reduced production costs, and obtained equal or better harvests compared with the farmers who did not use the disc tools.

“I want to improve my product; my compañeros and I, we all want to improve our product. The best thing that has happened to me is that now I understand better how to manage pesticides. We used to buy supplies and apply them by eye. Now we always measure and use only the precise amount needed. We used to apply a few anti-blight products together; now we apply one at a time and change to another in the next application. This new method is important for health and health is essential for work and for a better harvest at a lower cost” says farmer William Paredes in Huambaló (Tungurahua, Ecuador), with respect to use of the disc tool.

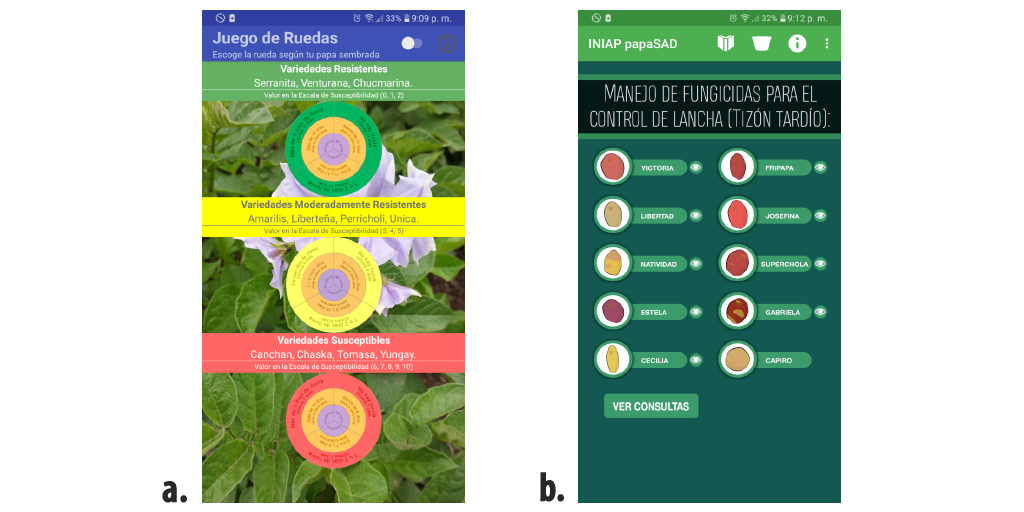

To attract young farmers, CIP and the National Institute for Agricultural Research (INIAP) of Ecuador have created a couple of disc-tool-based mobile apps and a video. The idea is that farmers can use an app on their cell phone, without accessing the Internet, to decide whether a particular potato crop needs an application of fungicide, in accordance with the specific variety as well as local environmental conditions.

Training programs on late blight management are recommended so that farmers can learn how to use the disc tools. Farmers need basic knowledge about the disease (for example, symptoms on the foliage), the resistance of the varieties to late blight, and the types of action of fungicides. Materials previously developed by CIP can be useful in implementing these training programs. Finally, the disc tools can be adapted to other regions. It is important to know each variety’s resistance to late blight and then the disc tools should be tested under local conditions, to make adjustments, if necessary, in coordination with local experts.

“I am proud to see that after several years of brainstorming on how to design a simple decision-support tool farmers can use to control potato late blight, the idea has materialized in an innovative tool that can be disseminated to farmers in other regions around the world,” says CIP research director Oscar Ortiz, recalling the early meetings to design this tool.

We would like to thank the following individuals for their collaboration with our research: C. Tello, X. Cuesta, J. Rivadeneira, J. Ochoa, D. Peñaherrera, J. Suquillo, F. Yumisaca and C. Sevillano of the National Agricultural Research Institute (INIAP); D. Caballero and A. Inca of the Polytech High School of Chimborazo (ESPOCH); and M. Haro, J. Miranda and L. Narváez in Ecuador. We are also grateful for contributions from J. Arias of the Daniel Alcides Carrión National University (UNDAC) and A. Guerra and P. Flores in Peru, as well as many others who participated in this research.

This work was financed and executed as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas and received support from the CGIAR Trust Fund. Financial support was also provided by the European Union through the Innovation for Food Security and Sovereignty in the Andes (IssAndes) project and the OPEC Fund for International Development.

Willmer Perez and Jorge Andrade-Piedra, with contributions from Oscar Ortiz, Nancy Panchi, Claudio Velasco, Jeff Bentley and James Stapleton