Farmer empowerment

Enabling progress and resilience in Malawi

Agriculture is the lifeblood of Malawi, responsible for more than 80% of its employment and 90% of foreign exchange. Yet population growth, low soil fertility and climate change have left millions of small-scale farming families unable to produce enough food and more than half the population in poverty. Scientists at the International Potato Center (CIP) and other CGIAR centers have developed innovations to help farmers improve their harvests and cope with crop threats such as drought, pests, and diseases. But getting the right tools to the farmers who need them is still a challenge.

Researchers from seven CGIAR centers are working with partners to adapt and disseminate tools and approaches to help Malawian families produce more nutritious food, build climate resilience, and overcome poverty.

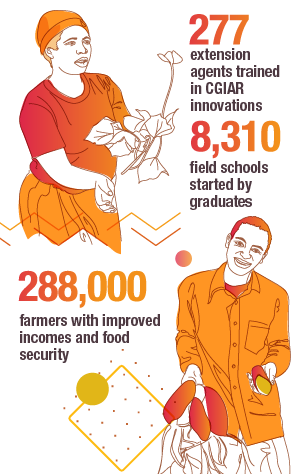

In coordination with the Deutsche Gesselschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), they designed a 13-week training course for extension agents that ranged in subjects from potato and sweetpotato cultivation to integrated farm management and agroforestry. Though COVID-19 curtailed coursework in 2020, 277 extension agents were trained between 2019 and early 2020 and, through collaboration with a consortium of NGOs, these support staff would go on to reach 288,000 farmers.

The training is part of a project called KULIMA, which means “promoting farming in Malawi” in the Chichewa language. Using the FAO farmer field school method – a participatory approach that CIP adapted for potato and sweetpotato more than a decade ago – extension agents work closely with facilitators and farmers to identify and promote innovations appropriate for their area. The benefits ripple outward, as each agent organizes field schools in 30 communities, with 30 participants each of whom, in turn, train more farmers.

“Within two years, I reached 900 farmers. That wasn’t happening before,” says KULIMA course graduate Michael Chome.

Malawian farmers mostly grow maize, which can be susceptible to drought and pests, so Chome and colleagues promote crop diversification and facilitate access to improved crop varieties, fertilizer, and other inputs. Farmers in Mulanje district, where Chome works, have begun to adopt crops that were rare a few years ago, such as potato, sweetpotato and banana. The addition of these foods is transforming family diets, economies, and resilience among smallholder farmers.

Inclusive transformation

Extension agent Rostina Lostina Banda observes that the KULIMA courses emphasized engaging women, which has increased its effectiveness. “There are more women farmers than men in Malawi, so we need to empower them and help them adopt innovations that can increase their food supply and incomes,” she says.

Adopting the right crops and varieties can be transformative, as countless cases confirm. Maxwell Nkhoma struggled for years to earn a living from maize and tobacco until he started growing orange-fleshed sweetpotato. He earned enough from selling this crop to buy a minibus, which he uses as a taxi. The combination of sweetpotato sales and taxi earnings enabled him to build a new house within three years.

A 2019 adoption assessment found that 31% of Malawian farmers grow orange-fleshed sweetpotato, just a decade after CIP and partners began promoting the crop there. Meanwhile farmers in Malawi’s northern region have been switching from tobacco to potato, doubling their earnings in some cases. Under an Irish Aid project, CIP trained 83 seed producers, who sold quality planting materials of potato and sweetpotato to almost 39,000 households in 2020. Those sales generated more than USD 125,000 – an average of USD 1,506 per farmer – a significant sum in a country where per capita GDP is about USD 500. Between 2016 and 2020, this project helped more than 126,000 households (nearly 60% of them female-headed) adopt climate-resilient potato, sweetpotato and cassava varieties.

Taking innovations to scale

Though courses were suspended in 2020, the extension agents trained in 2019 and early 2020 established farmer field schools across the country, and the innovations they’ve disseminated are improving lives. Since population growth and climate change will only intensify the challenges Malawi’s farmers face, CGIAR scientists are developing more effective innovations while supporting the training and evaluation of the latest technologies available in the field.

By producing a new generation of climate-smart technologies while building local capacity to take such innovations to scale, CGIAR is strengthening smallholder farmers’ productive capacity and resilience and contributing to food system transformation in Malawi.

Funders: CGIAR Trust Fund donors; European Union; Irish Aid.

Partners: ActionAid Malawi; Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT; Catholic Development Commission in Malawi; Centre de Coopération Internationale en Recherche Agronomique pour le Développement; Chancellor College, University of Malawi; Deutsche Gesselschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit; Evangelical Association of Malawi; Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center; International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics; International Food Policy Research Institute; International Institute of Tropical Agriculture; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development, Malawi; Plan International UK; Self Help Africa; L’Université de Liège; World Agroforestry; World Fish Center.

Associated CGIAR Research Programs or Platforms: Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security; Roots, Tubers and Bananas.