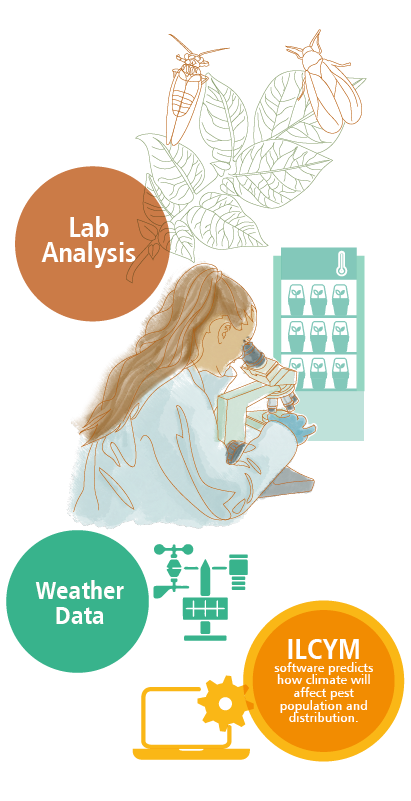

To understand where and when the risk of pests is growing, scientists at the International Potato Center (CIP) developed a software package that scientists and non-experts can use to understand how climate change is affecting pest distribution and populations. The program is called insect life cycle modeling (ILCYM), and an upgraded version was released in 2021 along with a website where people can download the program and user’s manual for free.

ILCYM software uses lab-collected data to determine how temperature affects an insect’s growth, reproductive rate and survival, and then combines that information with meteorological data from weather stations or international services to produce risk analyses and maps indicating where specific pests are most likely to become established or more abundant. This information has enabled people in government agencies and organizations to help farmers successfully control emerging threats.

According to Jan Kreuze, leader of CIP’s Crop and Systems Sciences Division, researchers have used ILCYM to predict pest risk in potato, maize, cassava and sweetpotato in East Africa and South America, where the results contributed to efforts to control threats to food security and the incomes of small-scale farmers.

“ILCYM is an important component of our One Health approach to pest and disease management,” says Kreuze. “By increasing its use and making its information available to more farmers, we can help prevent millions of dollars of crop loss, improving food security and incomes globally.

Andean emergency

ILCYM is gaining a foothold in the Andean region, thanks to a Spanish-language version of the user’s manual and workshops for government and non-government scientists in 2020 and 2021.

“ILCYM helps us understand the risk that pests pose in the present and future under climate change, which helps us prepare for those threats,” explains Santiago Reyes, an official at the Ecuadorian phytosanitary and zoosanitary regulation and control agency, Agrocalidad.

Reyes cites the example of the potato psyllid, a small insect that causes massive crop destruction. Originally from North America, the psyllid was first reported in northern Ecuador in 2016, by which time it had infested much of that region’s potato fields and devastated its tamarillo (tree tomato) production.

After the psyllid was discovered in Ecuador, CIP scientist Heidy Gamarra used ILCYM to produce risk indices and maps for the region and helped raised awareness of the threat it poses in Ecuador, Colombia, Bolivia and Peru, where she led workshops and helped researchers use ILCYM. This inspired the creation of a community of practice (CoP) by people at government agencies, universities and NGOs who now use ILCYM to model the risk of various crop pests in Ecuador.

“ILCYM allows us to take early action, before a pest population explodes,” says Emerson Jacome, a researcher at Ecuador’s Universidad Técnica de Cotopaxi and CoP member. “The better we understand a pest problem, the more easily we can find solutions for it.”

Sustainable solutions

Jacome and Reyes observe that farmers often respond to new pests with excessive pesticide use, which can threaten human health and the environment, and result in pesticide-resistant pests. Ecuadorian officials thus designed an integrated management protocol for the potato psyllid, promoting measures such as monitoring, crop rotation and insect traps before pesticide use. That approach reduced the potato growing area affected by the pest from more than 53,000 hectares in 2016 to less than 18,000 ha in 2021.

“ILCYM enables us to focus our monitoring efforts and integrated pest management activities in areas where the risk of a pest is highest,” notes Reyes, who explains that he plans to use the program to strengthen the management of avocado, maize and citrus pests.

Gamarra notes that the program can help farmers reduce pesticide use by as much as 50%. She explains that CIP is working with partners to develop a more user-friendly phone app that extension workers and farmers can use as a decision support tool. “We are expanding this tool to cover more pests and want to make it accessible to more people in more countries,” she says.

“The goal is to support ILCYM’s use by plant protection organizations in Asia, Africa and Latin America to be better prepared for future pest outbreaks and guide actions that reduce crop loss,” adds Kreuze.

Funders: Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung/Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit; CGIAR Trust Fund donors; Cooperación Española.

Key partners: Agrocalidad; CEFA; Centro de Desarollo Integral de Comunidades (CEDINCO), Perú; Fomento de la Vida (FOVIDA), Perú; Fundación PROINPA, Bolivia; Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Agropecuarias, Ecuador; Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología del Perú; Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria del Perú; Universidad Técnica de Cotopaxi, Ecuador.

Associated CGIAR Research Program: Roots Tubers and Bananas.