Sweetpotato biodiversity can help increase climate-resilience of small-scale farming, according to the findings of a study undertaken by researchers from the French public research institution IRD, CIRAD (Agricultural Research for Development), and the CGIAR center, the International Potato Center (CIP). The findings of this global analysis of the intraspecific diversity of the sweetpotato—one of the world’s most important food crops, demonstrate the role of this genetic diversity in the productivity and resilience of food and agricultural systems in the face of climate change. The results were published on 5 October in the Nature Climate Change journal.

Sweetpotato biodiversity can help increase climate-resilience of small-scale farming, according to the findings of a study undertaken by researchers from the French public research institution IRD, CIRAD (Agricultural Research for Development), and the CGIAR center, the International Potato Center (CIP). The findings of this global analysis of the intraspecific diversity of the sweetpotato—one of the world’s most important food crops, demonstrate the role of this genetic diversity in the productivity and resilience of food and agricultural systems in the face of climate change. The results were published on 5 October in the Nature Climate Change journal.

Climate change poses a threat to the world’s subsistence crops. Heatwaves, which are likely to intensify according to climate evolution predictions, are generating levels of heat stress that are damaging to agricultural production. Identifying resistant crop varieties is therefore crucial to ensuring people’s food security and farmers’ resilience. To date, many studies have been conducted on varietal improvement, which involves developing and selecting plants with the required characteristics. Few, however, have examined intraspecific diversity, which is defined as the degree of genetic variety that exists within the same species.

For the present study, the international team focused on the sweetpotato – the fifth most produced crop in the world, after corn, wheat, rice, and cassava. This tuber is grown for its hardiness and tolerance to climatic shocks, and has great potential to help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted by the United Nations as part of the Horizon 2030 Agenda: it is grown in areas prone to erosion to protect agricultural land (SDGs 12 and 15); it has a high nutritional value, as well as higher content than most staple foods in vitamins A and C, calcium, iron, dietary fibre, and protein (SDGs 2 and 3); its flexible planting and harvesting schedules mean it is less labour-intensive to grow and thus is particularly adaptable to human migration (SDGs 10 and 16).

Traditional local varieties perform well under heat stress

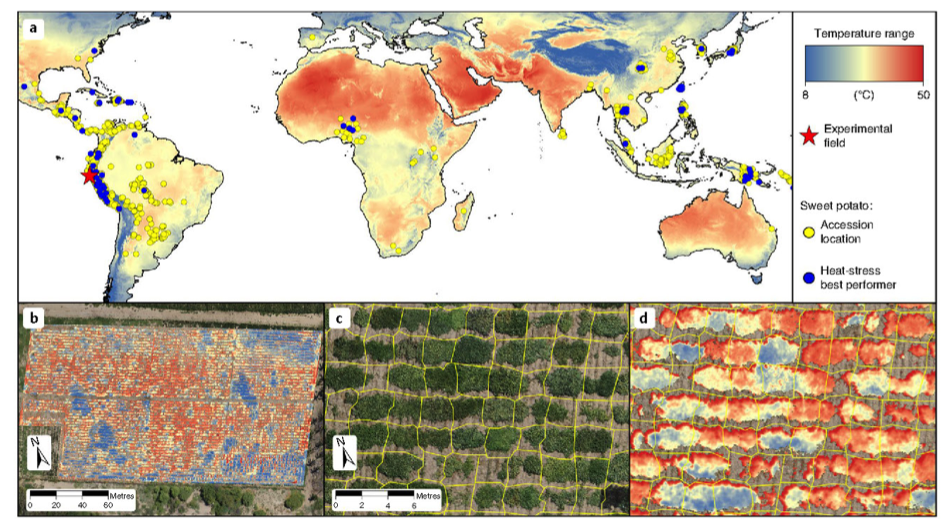

As part of CGIAR’s research program on roots, tubers and bananas (RTB), the researchers assessed the heat-stress tolerance of 1,973 different varieties of sweetpotato from the CIP’s sweet-potato ‘genebank’. The collection of cultivars from 50 different countries comprised modern and traditional varieties, as well as breeding lines, developed in vitro and then planted in fields irrigated under controlled conditions on a 2.5 ha test site in the coastal desert region of north Peru. Analysis of the roots and foliage data allowed the effect of repeated exposure to extreme temperatures – greater than 35°C – on the plants’ performance to be measured.

Result: “132 cultivars, of which 65.9% were traditional local varieties, demonstrated good heat tolerance. These are therefore promising candidates for selection as high-yield, heat-tolerant varieties,” explains Bettina Heider, a researcher with CIP and lead author of the study.

“This mass screening, carried out on an unprecedented geographical scale (America, Africa, Asia), proved crucial to identifying the heat-stress tolerance characteristics of the sweetpotato, for the purpose of a deeper molecular characterization of specific genes,” explains Olivier Dangles, an ecologist at IRD and co-author of the study.

“Intraspecific diversity – the result of hundreds of years of co-evolution between farmers and their crops – is proving critical in the face of climate change,” he continues. “It emphasizes the role of agrobiodiversity in the resilience of tropical agricultural systems.”

Farmers will need help to adapt

“Our results also suggest that the temperature of the canopy and the level of carotenoids could be the appropriate markers for selecting heat-stress tolerant lines,” adds Emile Faye, researcher in spatial agroecology at CIRAD. “However, participatory experiments need to be conducted in different contexts, to test the efficacy and economic viability of the varieties identified.”

Intraspecific diversity offers more options to farmers, therefore, for managing climate risks and increasing the resilience of their farming systems. The study authors recommend that this knowledge be shared with farmers, so that they adopt high-yield varieties that also offer higher nutritional value.

Press contact

- Viviana Infantas, Media and public relations specialist, International Potato Center: cip-cpad@cgiar.org; +51 959 631 118

- Researchers: Bettina Heider, researcher at CIP, Peru / heider@cgiar.org; Olivier Dangles, ecologist, assistant deputy director of science at IRD, in charge of science and sustainability / olivier.dangles@ird.fr; Emile Faye, researcher in spatial agroecology at the UPR HortSys research unit of Cirad / emile.faye@cirad.fr

Reference

Bettina Heider, Quentin Struelens, Emile Faye, Carlos Flores, José E. Palacios, Raul Eyzaguirre, Stef de Hann, Olivier Dangles, Intraspecific diversity as a reservoir for heat-stress tolerance in sweetpotato. Nature Climate Change, October 5, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-00924-4

Further information

CIRAD is a French agricultural research and international cooperation organization working for the sustainable development of tropical and Mediterranean regions.

Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development) is an internationally recognised multidisciplinary organisation, working mainly in partnership with countries in the Mediterranean and intertropical zone.

The International Potato Center (CIP) is a research-for-development organization with a focus on potato, sweetpotato and Andean roots and tubers. It delivers innovative science-based solutions to enhance access to affordable nutritious food, foster inclusive sustainable business and employment growth, and drive the climate resilience of root and tuber agri-food systems. Headquartered in Lima, Peru, CIP has a research presence in more than 20 countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. www.cipotato.org

CIP is a CGIAR research center, a global research partnership for a food-secure future. CGIAR science is dedicated to reducing poverty, enhancing food and nutrition security, and improving natural resources and ecosystem services. Its research is carried out by 15 CGIAR centers in close collaboration with hundreds of partners, including national and regional research institutes, civil society organizations, academia, development organizations and the private sector. www.cgiar.org

RTB is a partnership collaboration of five research centers, with decades of experience in these crops on different continents, including four CGIAR research centers (Bioversity International, the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, the International institute of Tropical Agriculture and CIP). By working with more than 360 other partners, these five centers mobilize complementary expertise and resources; avoid duplication of efforts; and create synergies to increase the benefits of their research for smallholder farmers, consumers and other stakeholders.

Commentaries on the publication:

Tapping into farmers’ bounty to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (Olivier Dangles)

Plant agrodiversity to the rescue (Samuel Pironon and Marybel Soto Gomez)