A big hit with farmers, a big hitter against late blight.

Late blight is a devastating fungal disease that affects plants in the Solanaceae family, which includes potatoes and tomatoes. In 2022 alone, it caused an estimated global loss of $6.7 billion1 in yield losses and control costs, wiping out entire harvests of subsistence farmers who depend on potato for their food security and livelihoods. In Peru, where potatoes originated, warmer temperatures mean that late blight is spreading into higher altitudes in the Andes – traditional potato-growing areas that historically have been free of the disease. Such breeding efforts also benefit farmers in Africa and South Asia, where late blight is a recurrent disease and resistant potatoes would reduce the need for expensive fungicides used to control it.

“Late blight is the potato disease that people may know as it caused the Irish Potato Famine in the 1840s and it has not gone away,” said Hugo Campos, CIP Deputy Director General for Research. “Developing resistant varieties is a priority for Peru to strengthen the resilience of smallholder producers against the devastation it can cause, starting with those from the thirteen districts in the central highlands that have participated in the trials over the last four years. These communities are already familiar with Mathilde and appreciate her resistance.”

Finding the genetic keys to put the past in the future.

CIP scientists have worked over several years to develop varieties that are resistant to late blight by identifying and transferring traits found in crop wild relatives and then working on ways to cross them into cultivated ones. Crop wild relatives are the distant ancestors of today’s cultivated crops which grow untended in different ecologies such as tropical forests, highland prairies, wetlands, and deserts. This has resulted in a wide range of genetic diversity in their populations as they constantly evolve to threats such as climate change and new crop pests and diseases, developing traits that can be used to build resilience in today’s food systems.

“Going back to the past to build resilience to the future through breeding programs that target modern threats like late blight is like opening a treasure chest full of genetic keys that could contain the traits you need,” said Thiago Mendes, Plant Breeder, CIP. “Finding them can be a long, laborious process – we worked for several years to find traits resilient to late blight studying samples held in the CIP genebank – as most wild species have not been characterized yet.”

Mendes explains that when you find the trait you need, crossing wild and cultivated species is not easy since their genetic makeup is different despite being related. But when varieties like Matilde are developed, the time, effort, andresources spent are worth it to the farmers.

A testing time: Out of the lab into farmers’ fields.

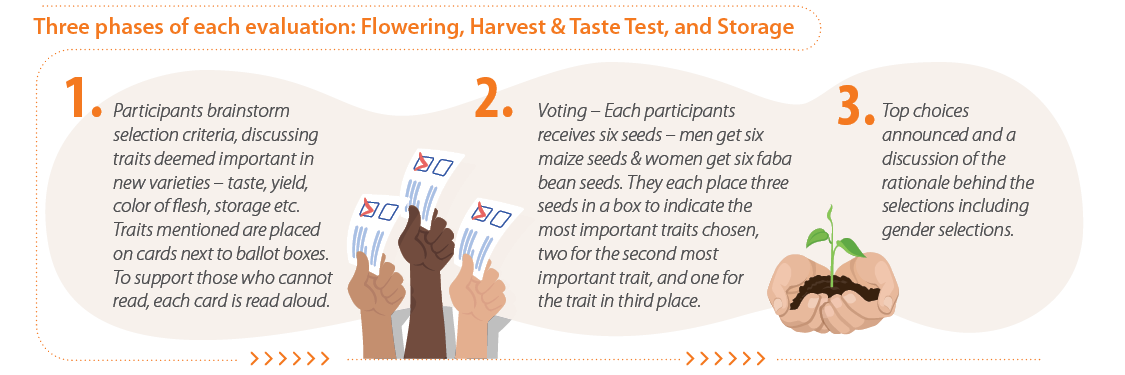

Field trials resulted in varieties developed through the breeding program that exhibited significant resistance to late blight, surpassing that of popular local varieties even without the use of fungicides. However, the development of resistant varieties alone does not guarantee their adoption by farmers. These varieties must work in the local context, appealing to the farmers and consumers who will cultivate, consume, and buy them.

“It is only when these factors align, that the benefits of these varieties can truly take root and make a positive impact within the communities – it is not just about yield,” said Maria Scurrah, Plant Geneticist, at Grupo Yanapai, a local implementation partner who acted a bridge between the plant breeders and the farmers during the participatory evaluation phase. “We are essentially asking farmers to take a risk by moving from a popular local variety, like Yungay, to try something unknown. If it does grow well, or no one wants to eat it or buy it, that could be devastating for their family’s food security, and the only way to find out is to ask them.”