Potato is India’s third most important crop, after rice and wheat, in terms of human consumption. India is also the second-largest potato producer globally. Production increased fivefold from 8.3 million metric tons in 1980 to 50 million in 2020. Increasing farmer access to quality, affordable seed is critical to build on this success.

“Apical Rooted Cuttings(ARC) technology was introduced here in 2019, so it is really quite new,” said Ravindra, Project Manager, CIP India. “We think it is going to change the whole seed sector here– CIP has put clean seed in the hands of 50,000 farmers around the world, boosting yields and incomes by as much as 50%. The government here is looking at that and early trials we did in Assam and starting to see its potential here, and it’s huge.”

Currently, seed production in India is dominated by large companies based in Punjab that use aeroponics to produce cuttings – a way of producing plantlets without soil. With projects in Haryana (north), Meghalya (northeast) and Karnataka (south), the ARC initiative plans to put seed production back in the communities where it is needed.

High-tech approaches like aeroponics require high start-up capital. Also, the current seed system is based 2,000km from Haryana, Meghalya, and Karnataka and transportation costs add 30% to the seed price. Seed already accounts for 50% of production costs for farmers, which means they are more likely to reuse their seed, increasing the risks of contamination from pests and diseases over time. A low-tech, low-cost alternative like ARC can put quality seed production of early-generation seed into the hands of the farmers.

What are Apical Rooted Cuttings?

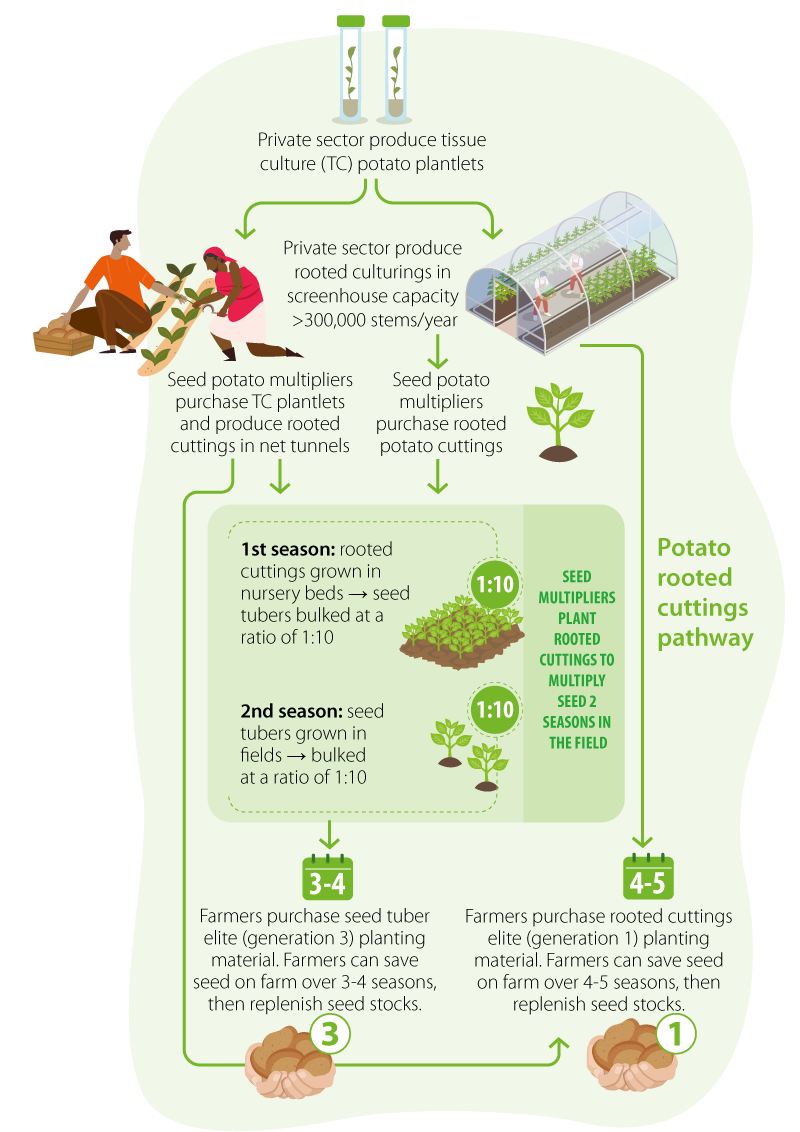

Apical rooted cuttings are produced in a screenhouse from tissue culture plantlets grown under controlled sterile conditions to ensure they are disease-free. Each plantlet can produce more than 100 rooted cuttings which are then bought by seed producers who multiply the seed in the field. Each cutting can produce 10-20+ tubers which , after a further round of multiplication, can be sold as certified seed to farmers.

“Apical Rooted Cutting (ARC) has the potential to be a game-changer for smallholder potato farmers in India,” said Dr. K.M. Indiresh, vice-chancellor and director of education at the University of Horticultural Sciences, Bagalkot Karnataka, India. “By reducing cost and enhancing accessibility to quality seeds, ARC can significantly contribute to the prosperity and sustainability of smallholder potato farmers in the country.”