“Increasing farmer access to quality seed is the low hanging fruit among options for improving food production and incomes in these crops,” says Ian Barker, Director of the International Potato Center’s (CIP) Global Potato Agri-food Systems Program.

The CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB) convened a multi-disciplinary team that launched a virtual Seed Systems Toolbox in 2021, to help researchers, practitioners and policy makers improve farmers’ access to quality seed. Vegetatively propagated crops are also a focus of the new multi-million dollar CGIAR Seed Equal Initiative. In the meanwhile, successful models are available in Africa, such as potato and sweetpotato seed systems in Kenya, which offer lessons for other countries.

Planting prosperity

Potato is Kenya’s second most important staple crop after maize, grown by more than 800,000 farm households, thus providing food for nearly 4 million household members, and supporting an additional 2 million active in the value chain. The country’s annual potato production is worth more than USD 430 million, and smallholders are responsible for 83% of it, but average yields of 6-10 tons of potatoes per hectare are holding most of them back.

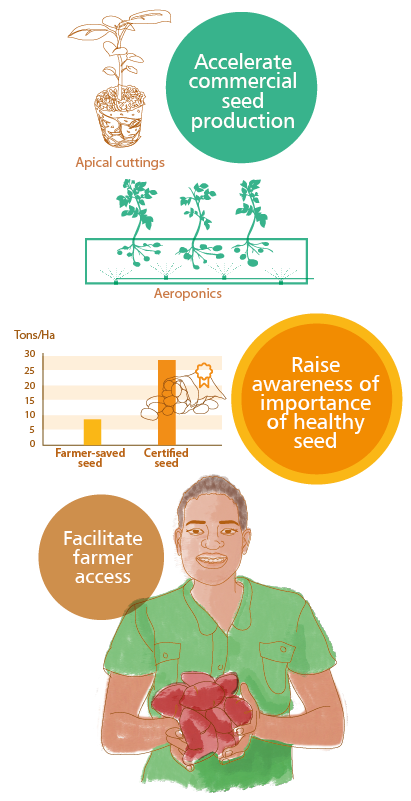

CIP has spent more than a decade working with government partners, companies and farmers to catalyze the production and use of commercial seed. Seed production takes time, because each plant produces just 6-10 seed tubers, compared to hundreds of seeds per grain plant. To overcome this challenge, new technologies have been promoted to accelerate production, such as aeroponics and rooted apical cuttings. While aeroponics is used by large operations, such as the Kenya Agriculture & Livestock Research Organization, apical cuttings can also facilitate the decentralization of commercial seed production.

Those technologies contributed to a more than 20-fold increase in certified seed potato production in Kenya from 2009 to 2018, and it continues to rise. Whereas production was less than 1% of what farmers planted in 2009, by the end of 2021, enough certified seed was being produced to plant in 9% of Kenya’s potato fields. And since farmers only need to replace their seed every three or four years to maintain good yields, 9% is enough to meet 27% to 36% of farmers’ seed potato needs.

“A decade ago, there were just a few certified seed potato producers in Kenya, but now there are 28, plus out growers who multiply seed on behalf of registered producers,” says Wachira Kaguongo, CEO of the National Potato Council of Kenya (NPCK), which promotes the use of commercial seed among farmers.

“Many farmers don’t buy certified seed because of the price and transaction costs, but interventions to decentralize production and distribution, such as NPCK’s ViaziSoko farmers’ app, are increasing its availability, while farmer awareness of its value is growing,” Karuongo explains.

Stella Mukiri, who farms one acre in Meru County, began growing potato to increase her income after her husband died. She first planted locally purchased potatoes but harvested only 750 kg. The next year, she purchased apical cuttings and grew her own seed potatoes, which produced 1,500 kg.

“My income from potatoes has allowed me to pay my child’s school fees, build a shed for my cows, and tile the floor of my home,” Mukiri says.

Reaping nutrition

Sweetpotato has the same seed challenges as potato, so CIP has made comparable efforts to increase production and use of quality sweetpotato planting material. This included providing technical support to the Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service (KEPHIS) to create a financially sustainable enterprise that produces virus-free starting material. In 2021, KEPHIS sold more than 70,000 vine cuttings to dozens of seed producers and organizations that used them to grow vines to sell or give cuttings to farmers. At the same time, CIP and county governments helped vine multipliers grow and distribute more than 3.4 million quality vine cuttings to families with young children, enabling them to grow pro-vitamin-A orange-fleshed sweetpotato.

Makei Mamo, a beneficiary in Isiolo County, grows sweetpotatoes and vines with members of a women’s group. They produce enough to feed their families and sell surplus sweetpotatoes and vines.

“Sweetpotato is improving our children’s nutrition,” Mamo says. “Due to demand, we will be expanding our vine multiplication to produce enough for the community and ourselves.”

As more farmers plant quality sweetpotato vines or seed potatoes, they too will reap better harvests and income improvements.

Funders: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; CGIAR Trust Fund donors; Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office; Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung/Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit; Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture; United States Agency for International Development.

Key partners: County governments of Baringo, Bungoma, Garissa, Isiolo, Meru, Nandi, Samburu, Taita, Tana River, Taveta and Wajir; Farm Input Promotions Africa; Kenyan Agricultural and Livestock Research Organization; Kenyan Plant Health Inspectorate Service; Kisima Farm, Kenya; Nandi Potato Farmers’ Cooperative Society; National Potato Council of Kenya; Stokman Rozen Kenya; Taita Papa; World Food Programme.

Associated CGIAR Research Programs: Roots Tubers and Bananas; Agriculture for Nutrition and Health.