A jumbo El Nino expected in the months ahead is likely to have significant effects on global potato crops – perhaps both positive and negative. Yet CIP researchers are harnessing strategies now to help offset losses and maximize yields in the face of an unknown set of variables.

A jumbo El Nino expected in the months ahead is likely to have significant effects on global potato crops – perhaps both positive and negative. Yet CIP researchers are harnessing strategies now to help offset losses and maximize yields in the face of an unknown set of variables.

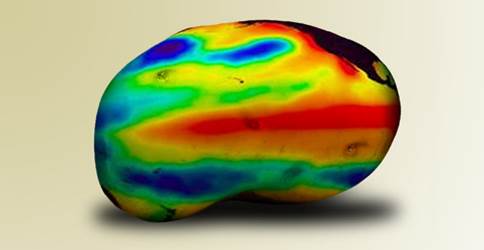

The full name of the climate phenomenon – the El Nino Southern Oscillation, or ENSO – is characterized by periodic increases and decreases in sea surface temperatures over the central and east-central equatorial Pacific Ocean, says Roberto Quiroz, leader of CIP’s crop systems intensification and climate change center of excellence, which looks at the interaction between climate and agriculture. When temperatures rise, it’s referred to as an El Nino cycle; when they drop, it’s a La Nina phase.

Broadly speaking, in an El Nino phase “some places will get more rain, and some will get more drought,” he says. And yet there are flukes in the forecast this year: for one, more moisture than usual is expected in the southern Andes, southern Peru and Bolivia, a predicted outcome at odds with historically drier conditions associated with El Ninos of the past.

“As change the composition of Earth’s atmosphere, we are getting more extreme [climate] events both in terms of frequency and intensity,” Quiroz says. These climate extremes can intensify the effects of naturally occurring events like ENSO.

While it’s impossible to say exactly how this El Nino will play out, centuries-old strategies practiced by smallholder farmers in the Andes offer models for adaptation from which researchers and farmers might learn as they move into the winter season.

When I came here from Panama 27 years ago, I realized farmers in Central America didn’t face the challenges the farmers in the high Andes face,” Quiroz says. “Here, extreme events are a constant.”

For example, hailstorms, frost or other extremes affect crops every year in the Andes – but because farmers expect them to occur, they plan for them “using a portfolio of options,” from planting at different elevations to planting myriad crops that not only rotate with the seasons but also take sudden climate shifts into account, a practice known as “multicropping “

Farmers “know there’s a difference of two or three degrees between the top of a hill and the bottom,” and they plant hardier crops lower down, he says. Or they might plant early varieties in one spot and later ones elsewhere. Even if an unusually early frost depressed yields on the early varieties, the late- or intermediate-blooming ones could help offset losses.

Through these efforts, “resilience is built into the system,” he says. And that resilience could mean the difference between life and death for those dependent on the farmers for food. To that end, it’s imperative that potato farmers pay attention to their local forecasts as they plan their winter planting and harvesting.

Ultimately, the goal is to learn to “manage for uncertainty,” in this El Nino cycle and in the changing global climate as a whole.

“A bad year for potato,” for example, “might be a good year for livestock,” Quiroz says.

“The world is now talking about climate-smart agriculture,” Quiroz adds. “There’s a lot we can learn from the experts. We need the wisdom of tradition as well as what the science tells us.”