As the global population approaches eight billion and climate change threatens farming in varied ways, enabling farmers to produce more food on limited farmland – without exacerbating agriculture’s environmental impact – is one of humanity’s great challenges.

One option for addressing that challenge is to incorporate potatoes into grain-based agricultural systems. Farmers in various Asian countries do this, but they’ve barely tapped the crop’s potential for increasing food availability and diet diversity. The sustainable intensification of rice or wheat farming systems by growing potatoes during the months when that land might otherwise be fallow can increase food production, income, and environmental benefits such as more efficient use of water and soil resources.

Efforts to help grain farmers use potato for sustainable intensification have included introducing innovations such as planting seed potatoes with zero tillage and using grain stalks as a crop cover or mulch. A study on the effects of those methods published earlier this year in Agronomy confirm their ability to enhance the potato’s potential for sustainable intensification and provides insights for taking them to scale.

Researchers from the International Potato Center (CIP) and partner universities reviewed 49 studies that included zero- or minimal-tillage or the use of rice straw mulch in potato farming, most of which were undertaken in Bangladesh, China, India or Indonesia. The review confirmed that those methods can not only increase a farm’s production and profitability, the lack of plowing or digging makes zero tillage less laborious than planting usually is, which reduces costs and facilitates adoption by female farmers. Farmers merely need to place seed tubers of early-maturing varieties (ready to harvest 70-90 days after planting) on the moist ground after a rice harvest and cover them with the rice stalks, as a straw or mulch, and within three months, they can harvest potatoes.

CIP scientist and first author David Ramírez observes that in addition to higher yields and profits, zero tillage and mulching can contribute to sustainability through improved soil health and reduced carbon emissions.

“Research shows that flooded rice paddies are responsible for 15 to 20 percent of anthropogenic methane emissions, and methane has 25 times the global warming impact that carbon dioxide does,” Ramírez explains. “Zero-tillage potato farming and mulching in rice-based agricultural systems, with a low level of inputs, are great ways to intensify food production while limiting greenhouse gas emissions.”

Farmers in India burn an estimated 14 million tons of rice and wheat straw annually, producing noxious air pollution during the dry months and contributing to climate change. By using that straw to grow potatoes instead, they could significantly reduce their carbon footprints.

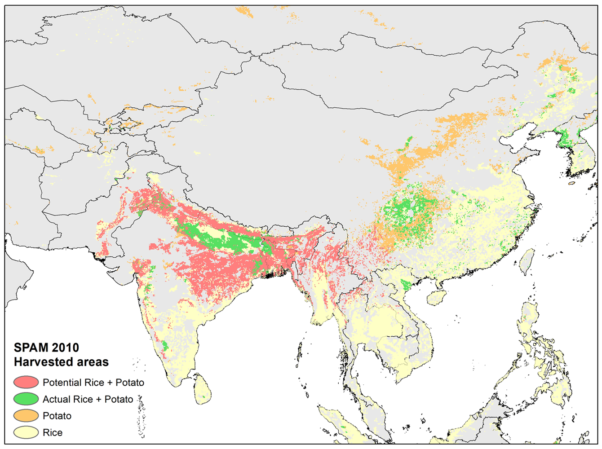

Currently, only two percent of Asia’s rice paddies are used to grow potatoes, so zero tillage and mulching haven’t yet had the impact on greenhouse gas emissions that they could. However, the study’s authors used Google Earth temperature data the Spatial Production Allocation Model (SPAM) to determine where potato could be introduced into rice-based systems. They estimated that a potato crop could eventually be integrated into more than 33 million hectares of paddies, or almost a quarter of Asia’s rice farming area.

CIP scientists have facilitated zero tillage and mulching to enhance potato production in India’s rice paddies with good results, and are currently promoting those practices in Bangladesh and Bihar, India. The researchers observe that any effort to promote sustainable intensification with potato should facilitate farmer access to quality seed potatoes of climate-smart, early-maturing varieties, such as the heat- and salt-tolerant varieties CIP and partners developed for the coastal lowlands of Bangladesh.

Jan Kreuze, leader of CIP’s Crop and Systems Science Division and a co-author of the study, observes that growing potatoes on top of the soil, in rice straw or mulch, should reduce the risk of soil-borne diseases and insects such as aphids, which spread potato viruses, thus reducing the need for agrochemicals. However, scientists have yet to collect data on pests and diseases in fields where farmers use zero tillage or mulching.

“This is something that future research should focus on, because it could reduce postharvest losses and the need for agrochemicals, which would benefit the environment” says Kreuze.

According to co-author Cecilia Silva-Díaz, there is also a need for further research to quantify how much zero tillage and mulching reduce greenhouse gas emissions, noting that such evidence could qualify farmers who use those approaches for climate change mitigation funds, which would facilitate taking them to scale.

“If we can promote an innovation that reduces carbon emissions, that’s a win; but if we can show farmers that these practices will help them increase production and deal with the waste that rice farming leaves behind, they will be more likely to adopt them,” Silva Díaz notes

As a growing number of Asian farmers try zero tillage and mulching, the article in Agronomy bodes well for their potential to enhance the potential of sustainable intensification to improve diets, incomes and natural resource use in Asia.

The research was supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) and CGIAR Trust Fund contributors.

Blog by David Dudenhoefer