A recent study from the International Potato Center (CIP) calls attention to downward trends in varietal diversity in major cropping systems in Asia and Africa. As climate change impacts continue to affect agriculture, these trends have significant (potentially worrying) implications for ensuring future yields and food system resilience around the world.

Published in the journal Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, and co-authored with scientists from the International Rice Research Institute and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, the investigators made novel use of big datasets from 44 countries in Asia and Africa for 11 major food crops, including potato and sweetpotato, over a 50 year period.

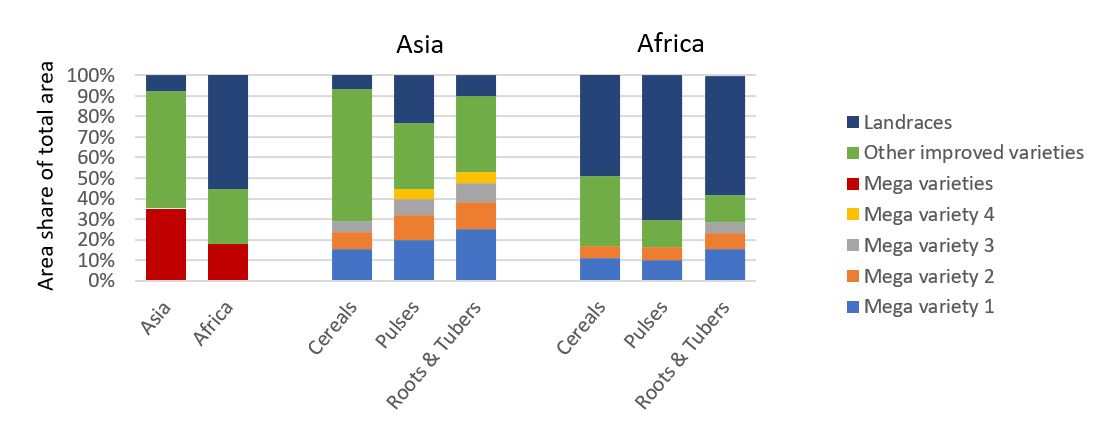

The research team found that declines in varietal diversity are linked to the spatial displacement of traditional landraces and that these trends are faster in Asia than in Africa (Figure 1).

However, the researchers were surprised to find a complicated relationship between crop improvement (breeding) and varietal diversity.

“Since the Green Revolution we have seen large investments in breeding resulting in an unprecedented number of modern varieties… that are subsequently released,” says Marcel Gatto, an agricultural economist at CIP. “A common assumption is that more breeding leads to more [variety] and thus more diverse agricultural systems. However, the link between crop breeding and cultivar diversity is not that straightforward.”

Co-author Stef de Haan, a senior scientist for Andean Food Systems at CIP, agrees. “The link is not simple. Some previously-released varieties (such as IR64 rice and Cooperation 88 potato) are quite persistent and have become megavarieties. And these megavarieties have proven very environmentally-flexible.”

While these megavarieties have substantially contributed to raising incomes, food and nutrition security, researchers are concerned with the longer-term impacts of growing less diversity. Lack of varietal diversity is strongly suggested to reduce agricultural resilience resulting in lower yields, a trend which is exacerbated by increased incidence of pests and diseases associated with climate change and monocultures.

While the research team acknowledges the rise in megavarieties, they were reluctant to identify or name one single factor that contributed to this rise.

De Haan believes breeding approaches to the marketplace has strong explanatory effect. “These varieties wouldn’t exist if there weren’t good markets for them to be sold. Markets look for efficiency, uniformity and year-round supply. They tend to work against diversity this way. Breeders naturally look to make genetic enhancement more efficient. While new breeding approaches are increasingly efficient, they also tend to rely on a narrower genetic base. Consequently, we pump less diversity into the system. We need diverse breeding approaches, investment in pre-breeding and biodiscovery, release procedures that embrace diversity and a better understanding of consumer preferences as food systems are transforming.”

Luck certainly also plays a role, as Gatto acknowledges: “Some varieties are developed at the right time and in the right place in the world. Discovering the drivers for these trends is a great avenue for future research.”

Both co-authors agree that creating awareness of the need for varietal diversity is a most important factor for governments, farmers and research institutions like the CGIAR.

“We need to provide an enabling environment and incentives to strengthen the use of diversity in breeding and in agrobiodiversity conservation programs while assuring that food supply chains absorb more varieties. This can be done and practical innovations towards this end exists. For example, in Peru and the Netherlands where the urban demand for potato and tomato varietal diversity has significantly increased during the last decade” says De Haan.

Gatto says value chains are another important factor “so these new varieties can get to markets faster and at lower costs.”

For farmers, Gatto and De Haan suggest working with them to conserve diversity and/or make it relevant to their income streams. “Varietal diversity is an effective backstop for building resilience in the wake of catastrophic events and in the face of current challenges from climate change. The same can be said for markets: diversity allows farmers to spread risks to buffer price fluctuations in scenarios where there is demand for diversity. We have seen that demand is shifting in many countries where consumers are becoming increasingly aware of food diversity. And we know from studies in the Andes that varietal diversity positively contributes to year-round food availability,” says De Haan.

Gatto concludes: “We need to strike a balance between food security [as largely satisfied by megavarieties] and diverse food systems that can withstand and produce under changing climatic conditions. New ideas, approaches, and partnerships are needed. That will be the challenge going forward.”

In the CGIAR’s transition to OneCGIAR (ongoing in 2021), the new structure will enable research synergies to provide many of these desired ideas, approaches, and partnerships.

The full article is available online and open access.