Potatoes for prosperity

A quarter of Kenyan potato farmers adopt more productive varieties

Africa’s first potato farmers were European settlers who introduced the crop in the late 1800s, but few Africans grew it before the mid-1950s. Since then, the tuber has taken off, with more than 25 million metric tons produced in Africa in 2017.

In Kenya, potato is now the second most important food crop after maize, grown by 800,000 small-scale farmers and generating employment for an estimated 2.5 million people along the value chain. Improved potato production has the potential to significantly boost farm incomes. While reality for most Kenyan farmers had long fallen short of that potential, recently introduced disease-resistant and heat-tolerant varieties are giving farmers the upper hand.

Superior spuds

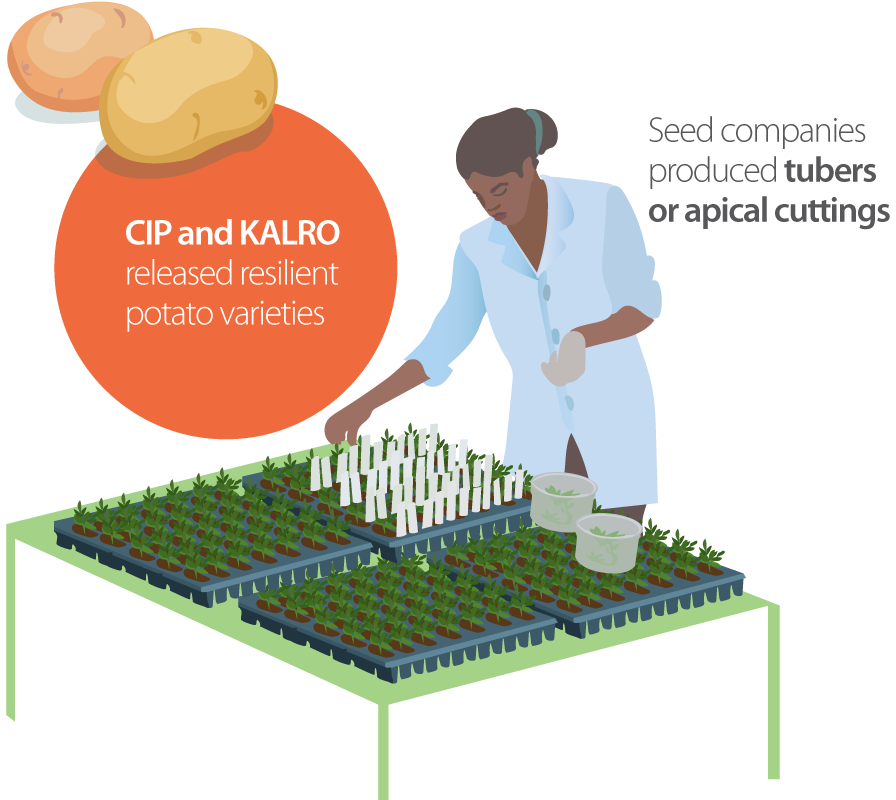

In Kenya, CIP partners with the Kenya Agriculture and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) to meet farmer demands for more resilient and higher yielding potato varieties with the attributes sought by consumers.

One such potato is Sherekea. Released in 2010, Sherekea is now grown by one-fifth of potato farmers in Meru county—a major producing area—and nearly one in ten nationally. Breeders selected Sherekea for its yield potential and resistance to late blight, a disease that destroys an estimated 30–60% of Kenya’s potato crop annually.

Climate-resilient Unica, another CIP variety released in 2016, thrives in both highlands and lowlands, rainy and dry areas, and resists viruses and late blight. Because Unica tolerates heat and water stress, it has been promoted in traditional and non-traditional potato producing areas, such as Meru and Tanita-Taveta counties. It is as productive as other varieties on less than a third of the rainfall.

Doris Kagendo Gikunda, a potato farmer in Meru County, likes that Unica produces plenty of large tubers in just three months. “Unica is very good when cooked, and it has a ready market. People in towns who prepare chips love it,” she said.

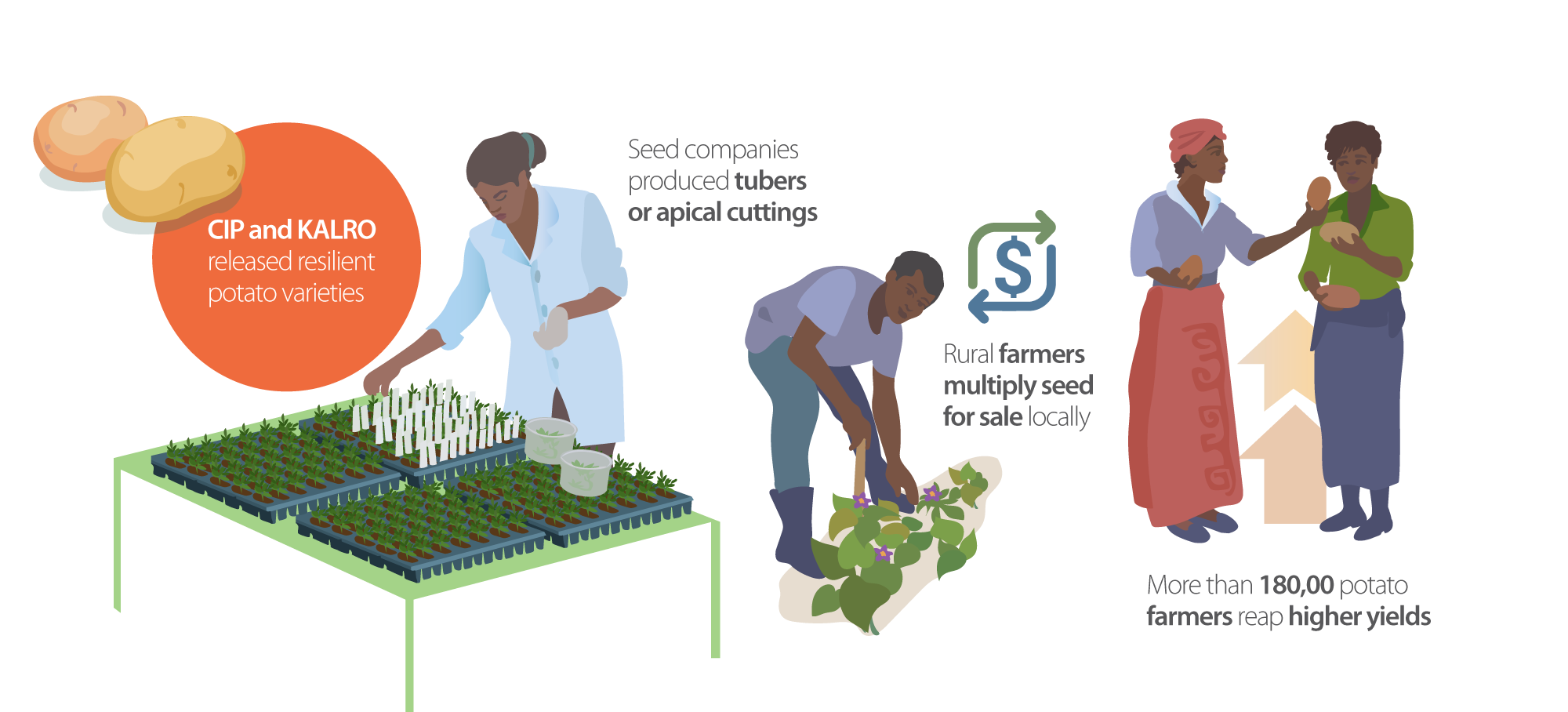

Sustainable seed systems

Because potato has a lower multiplication rate than grain crops, it can take up to 10 years to produce enough seed potatoes of a new variety for a sufficient number of farmers to start growing it. With the introduction to Kenya of new techniques like using rooted cuttings from potato plants as starting material, and training for small-scale seed multipliers and larger companies, the production of quality planting material has significantly accelerated in recent years.

This has been facilitated by public-private partnerships involving KALRO and a dozen seed companies, which have made seed production a more profitable activity and ensured the sustainability of the system. Thanks of these collaborations, a combination of parastatal and private sector enterprises now produce about 2 million metric tons of potato seed per year – five times what was available to farmers a decade ago – sold for about USD 2 million. In exchange for the rights to sell the varieties, KALRO receives 2.5% royalty of seed sales. The money raised helps fund the breeding of future varieties.

Kisima Farm, Kenya’s biggest seed producer, has scaled back production of Asante – until recently one of the country’s top varieties – to produce more Sherekea seed, which has become the company’s biggest seller. “Sherekea is now widely recognized as giving higher yields and being more late blight-resistant than Asante,” noted Jonathan Moss, Kisima Farm’s managing director.

Thanks to research and technical support over the last five years, NGOs and county governments have set up local systems to produce and disseminate quality seed to small-scale farmers more quickly. Consequently, nearly a quarter of Kenya’s potato farmers, some 180,000, now grow CIP-bred varieties. And since planting quality seed of improved varieties boosts yields, decision makers have taken notice.

“Our work has really opened the eyes of local leaders to the potential value of potato,” said senior scientist Monica Parker. “Over the last five years, more than 200 extension agents from nine county governments have trained farmers in the use of apical cuttings to produce seed potatoes, while CIP provided technical support to large seed producers, which led to at least 15 nurseries in Kenya investing in apical cutting production. This will accelerate the dissemination of the improved varieties and greater availability of quality potato seed in the coming years.”

Funders: Deutsche Gesellschaft for Internationale Zusammenarbeit; Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture; United States Agency for International Development.

Partners: Aroma; Farm Input Promotions Africa; Genetic Technologies International Limited; Kenya county governments of Bungoma, Elgeyo-Marakwet, Kiambu, Meru, Nakuru, Nandi, Nyandarua, Taita Taveta, and Uasin Gishu; Kisima Farm; Self Help Africa; Stokman Rozen Kenya; Taita Papa; Potato Empire; World Food Programme.

Associated CGIAR Research Programs: Agriculture for Nutrition and Health; Roots, Tubers and Bananas.