For thousands of years, farmers have chosen the best landraces to improve farm resilience and productivity

It’s a process breeders have systematized with the application of scientific knowledge. Now scientists need to take breeding to a new level to get nutritious sweetpotato into family diets while staying within the earth’s environmental boundaries, in the face of population growth, urbanization and climate change.

Targeted breeding has been central to the success of the International Potato Center (CIP) in improving the nutritional outcomes of nearly six million households in Africa and Asia since 2010. Extremely rare in Africa 15 years ago, orange-fleshed varieties are now sold in markets across the continent. CIP has catalyzed this process with disease-free planting material and capacity building of their national counterparts in 14 countries.

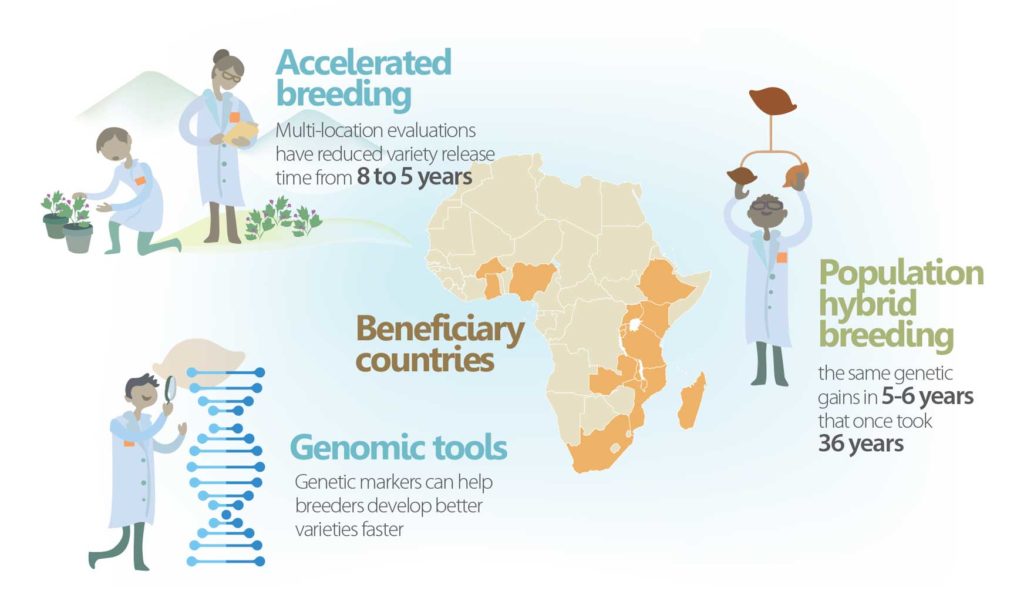

Over the last decade, CIP established three regional breeding platforms in Africa and made training available for national counterparts. The time needed to launch new varieties was cut from eight years to five and average yields of farmers who adopt those varieties have increased from 10.9 to 18.5 tons per hectare. These innovations have underpinned the release of more than 130 sweetpotato varieties in Africa—mostly of provitamin A orange-fleshed sweetpotato.

To ensure adoption, breeders need to develop nutritious, climate-resilient varieties that combine the most important traits for their target area. This multitrait selection requires compiling information on the preferences of men, women, children and industry processors, as well as laboratory data on the chemicals and genes responsible for traits.

Understanding gender preferences is key because women usually manage family diets and are increasingly involved in sweetpotato farming and marketing. CIP breeder Maria Andrade is working with a gender responsive breeding tool produced by scientists involved in the CGIAR Gender and Breeding Initiative.

“If we release climate-smart varieties which do not meet the needs of buyers, few farming families will adopt them. Farmers take a range of factors into consideration—taste, texture, nutrition and market value. If the buyers are women, breeding only for what men want will not help adoption,” she said.

Developing new varieties that combine climate resilience and the characteristics farmers and markets demand is essential but challenging, because sweetpotato is genetically complex. Its 90 chromosomes arranged in groups of six make understanding the functions of specific genes more difficult, compared to the paired chromosomes of crops like maize and rice.

In 2018, CIP and partner scientists made a series of breakthroughs that could revolutionize conventional sweetpotato breeding. They produced the first-ever reference genome for sweetpotato—a map of its genes and their locations on chromosomes—deepening understanding of this complex plant. They then created tools and protocols to standardize measurement of specific plant traits designed to facilitate implementation of genomics-assisted breeding approaches.

But most significantly, they demonstrated proof-ofconcept that hybrid breeding schemes could take sweetpotato improvement to previously unimaged magnitudes. Breeding parents in Peru and at African regional platforms have been divided into two distinct groups, because the progeny of crosses between genetically different parents tend to be superior to either parent—a phenomenon called hybrid vigor or heterosis. Multiple breeding trials have demonstrated the genetic gains achieved within 5-6 years can equal those which have traditionally taken 36 years.

More than propel delivery of nutritious sweetpotato to 15 million households by 2023—a CIP institutional goal—these innovations are laying the groundwork for sweetpotato breeding that will respond to the opportunities and challenges of an increasingly populous, climate-changing world.

Funder: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; CGIAR System donors through the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas; Department for International Development United Kingdom; United States Agency for International Development.

Key partners: Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa; Boyce Thompson Institute; Council for Scientific and Industrial Research-Crops Research Institute, Ghana; French Agricultural Research Centre for International Development; Michigan State University; National Crops Resources Research Institute; National Agricultural Research Organization, Uganda; North Carolina State University; University of Queensland.

Associated CGIAR Research Program/Platform: Roots, Tubers and Bananas; Excellence in Breeding Platform.