After battling the COVID-19 pandemic for more than two months, countries have begun relaxing lockdowns and people are slowly getting used to the new normal of masks, social distancing, and no large gatherings in their daily life. A third of the global population is still under some form of lockdown, down from half the global population in early April.

After battling the COVID-19 pandemic for more than two months, countries have begun relaxing lockdowns and people are slowly getting used to the new normal of masks, social distancing, and no large gatherings in their daily life. A third of the global population is still under some form of lockdown, down from half the global population in early April.

Lockdowns have been a stress test particularly for the global food system. The third of the world population still under lockdown after two months is a testimony to how well the global food system has performed. Apart from some isolated instances of supply chain breakdown during the initial days, the food system has delivered. Prices of some food products, especially perishables, have been higher in some places but that is to be expected when countries shut down their economies and close their borders. But the overall food price index, published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, declined in April by more than 3 percent.

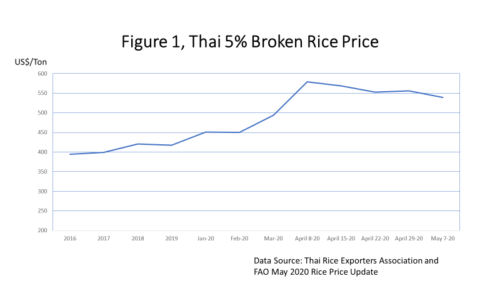

More importantly, the price of rice, considered the lifeline for most of the Asian population, also declined in April after sharp increases in March had stoked fear among rice-importing countries (Figure 1). Rice prices are still higher, have more to do with supply-demand fundamentals than with COVID-19 pandemic fear.

I have been following a few of WhatsApp groups of global rice traders that includes many prominent persons from the global rice-trading community. During the initial days of the lockdowns, these traders expressed quite a bit of anxiety and worried there would be a repeat of the 2007-08 food crisis. But many were also of the opinion that there is enough rice to go around and a crisis could be avoided if countries acted responsibly.

I have been following a few of WhatsApp groups of global rice traders that includes many prominent persons from the global rice-trading community. During the initial days of the lockdowns, these traders expressed quite a bit of anxiety and worried there would be a repeat of the 2007-08 food crisis. But many were also of the opinion that there is enough rice to go around and a crisis could be avoided if countries acted responsibly.

And, fortunately, countries have acted responsibly and this is reflected in the decline in rice prices, demonstrating a maturity of rice-exporting and -importing countries in the region. By contrast, during the 2007-2008 crisis, the Philippines was blamed for fueling a rice crisis through panic purchasing. But this year, its actions have been measured and thoughtful and avoided panic buying. This bodes well for the global food system and especially for the billions of rice eaters in Asia and elsewhere.

During this unprecedented global lockdown, the food supply chain has had to make some quick adjustments following the complete shutdown of food service establishments, including restaurants, cafeterias, and fast food chains. Produce supply had to be redirected from food services to supermarkets, where demand for food products skyrocketed. The switch has not been as easy as it sounds because of significant differences in the requirements between supermarkets and food services in terms of size, form, and preferences.

Potato is a great example of how the supply chain has struggled to make the switch from food services to supermarkets, particularly in Western markets, where food service demand for potato in the form of French fries and wedges, chips and other processed products constitute 60‒80 percent of total potato consumption. The sudden disappearance of a large proportion of the total demand created a glut in the back end, with millions of tons of fresh processing potatoes held in cold storage and an overstock of processed potato products.

For potato, processing varieties are well suited for domestic preparation and consumption. In fact, only a few potato varieties are suitable for both purposes. This was not a problem in developing countries, where potato is usually consumed fresh. The supply chains in these countries could easily handle a bit more volume during the start of lockdowns as people wanted to stock up at home.

Feeding the World with COVID-19

More and more countries will be relaxing their lockdowns in the coming weeks with restaurants, cafeterias and other food service establishments opening their doors to dine-in customers. Based on what we see in China and parts of Europe where lockdowns have been relaxed, customers are hesitant about returning to restaurants. It is likely that it will take several months to maybe a few years before restaurants return to pre-COVID-19 numbers.

But, more importantly, away-from-home consumption for most of the population will be influenced by fear and affordability, at least over the next several months. The world is now in deep recession, with hundreds of millions out of jobs, and it is impossible to predict a time and path for recovery. Apart from higher unemployment and lower disposable income, half a billion people will be pushed into poverty, according to OXFAM. These changes will shift the consumption patterns in developed countries from eating out to eating at home and in developing countries from high-value food products to staples such as rice, wheat, and potato. The global food system should adjust accordingly to meet the changing nature of global food demand in the short and medium terms.

But, more importantly, away-from-home consumption for most of the population will be influenced by fear and affordability, at least over the next several months. The world is now in deep recession, with hundreds of millions out of jobs, and it is impossible to predict a time and path for recovery. Apart from higher unemployment and lower disposable income, half a billion people will be pushed into poverty, according to OXFAM. These changes will shift the consumption patterns in developed countries from eating out to eating at home and in developing countries from high-value food products to staples such as rice, wheat, and potato. The global food system should adjust accordingly to meet the changing nature of global food demand in the short and medium terms.

Another source of concern is the highly consolidated food supply chain with few large dominant players in many developed countries. Over the past couple of months, hundreds of COVID outbreaks have been reported at meat packing and food processing plants across Brazil, Europe, Australia, and North America. A recurrence of outbreaks in these plants could severely disrupt the supply chain could trigger cascading long-term effects. By contrast, small and scattered food supply chains in developing countries are more resilient under the current circumstances and any operational disruption in some plants due to COVID-19 outbreaks is less likely to jeopardize the entire chain.

The core of our food system is represented by farmers and production agriculture, where everything begins. If production is lacking, then the rest of the supply chain will go haywire. Thus, it is critical that farmers have whatever they need to plant, harvest and market their crops. This includes labor, inputs, service providers, transportation, and markets, among other necessary goods and services.

The food system has delivered to date because there was enough production and stock of staples such as rice, wheat, and potato. The first planting season since the pandemic broke is starting now. Monsoon season, which starts in June, Asia needs to produce more than 500 million tons of paddy rice (more than 70 percent of the total production) by the end of the year. In the next few months, if everything goes well, including the weather, more than 110 million hectares of rice will be planted across Asia. During this planting time, backward supply linkages such as input supply (seed and fertilizer), labor and farm machinery service providers should operate at full strength for farmers to complete land preparation, seedbed nursery and transplanting on time. If monsoon rice production is on track, the harvest will fulfill the staple needs of half of the global population, including Africa and the Middle East. This rice production is also critical for the poverty-stricken eastern Indo-Gangetic plain covering eastern India, Bangladesh and Nepal, which will account for the bulk of the half billion people projected by OXFAM to be pushed into poverty due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Following the rice harvest, farmers in the region will plant other crops such as wheat, potato, maize, lentils, and some lowland irrigated rice. Governments should carefully analyze the problems associated with each of these commodities and ensure these problems are addressed before planting season. As discussed earlier, this will be a tricky year for potato. With restaurants, fast food chains and other food service establishments not expected to operate at full strength, the demand for fresh potato for home consumption will remain strong in the foreseeable future.

Faced with uncertain recovery in processing demand and old processing potato stocks in cold storage, potato farmers in North America and Europe have decreased their area devoted to growing processing varieties. Even if some farmers wanted to switch to table varieties, this would not be possible because of the non-availability of seeds for table varieties. But the potato situation can be managed with the South Asian planting season still six months away. Governments in South Asia should ensure that farmers have access to good-quality seeds, machines for planting and digging (in case labor problems persist) and cold storage facilities for storing tubers. A good harvest in South Asia can supply fresh potato for the rest of the world.

Each country, whether developed or developing, faces a unique set of issues for its food system under this pandemic. It is a no brainer that food systems need to be functional from farm to fork if the world has any chance of beating the virus. Countries need to be proactive rather than reactive in attempting to solve these problems because of the time-bound nature of production agriculture. Countries should also realize that this is a global pandemic and requires a global response. Any unilateral action by one country to restrict agricultural trade to protect domestic food security could be strongly counterproductive.

Blog by Samarendu Mohanty, Asia Regional Director