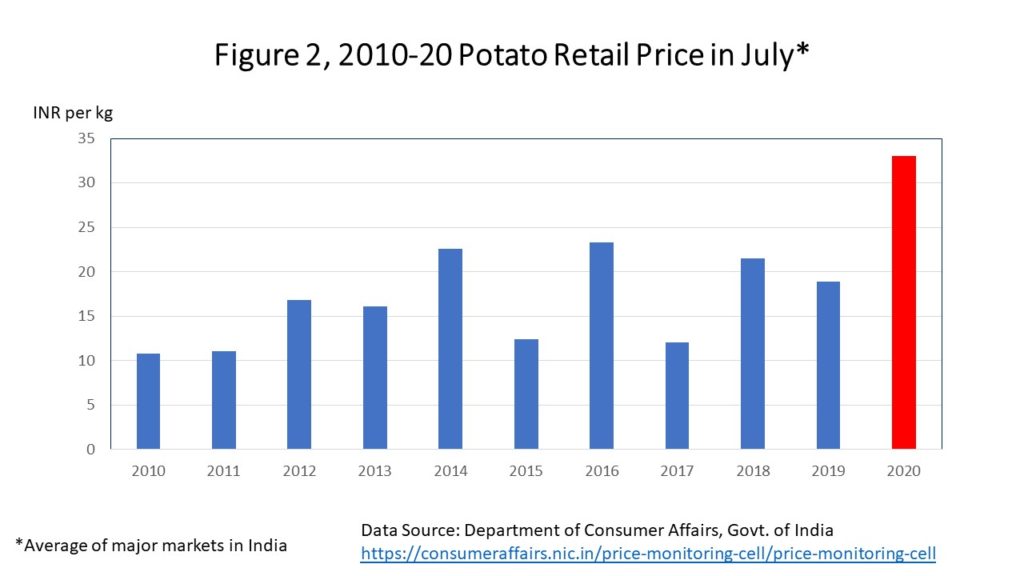

Potato prices in India started rising in December 2019 due to the delay in harvesting the early rabi crop (Figure 1). Although they fell a bit in February and March with the arrival of the new harvest, they have remained higher than average prices during the same period in previous years due to less area planted, lower yields and transportation issues.

Farmers in the top two potato-growing states, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal, planted less area in response to lower prices in 2019, while recent harvest yields were adversely impacted by incessant rains. The COVID-19 national lockdown in late March affected the harvest and transportation of potato to cold storage in many states due to labor shortages and restrictions on movement. According to the Indian Express in May 2020, 25% less potato had been placed in cold storage in March and April this year compared to the storage amounts a year earlier.

The supply problem and rush of people to stock up on potato because of its long storability created a spike in prices in late March and early April. Even the non-potato-consuming southern states saw prices increases.

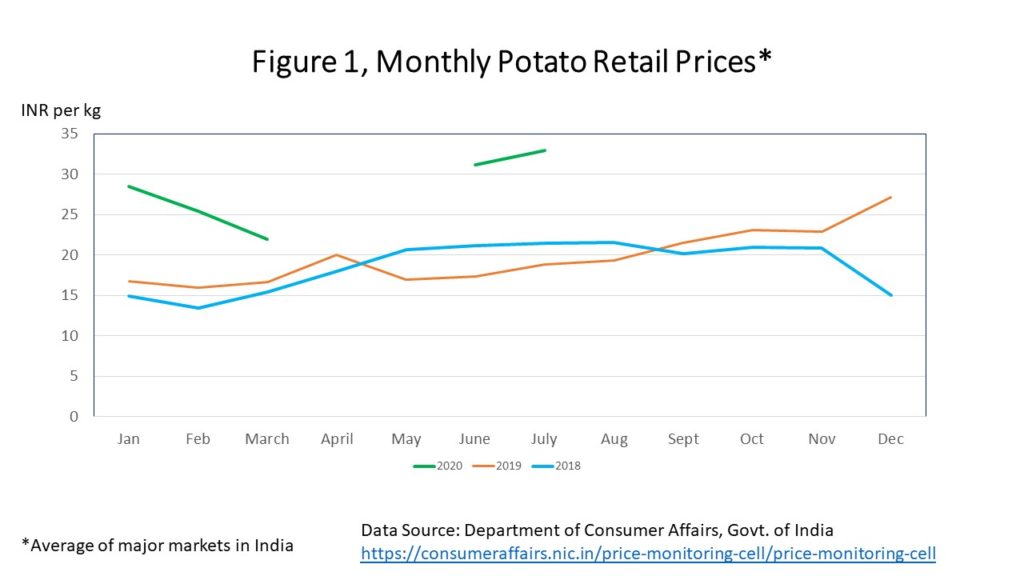

But the price spike was short-lived as demand softened due to the closing of restaurants, fast food outlets and other food service establishments in late May. When the economy opened again in late June, prices started rising again as demand from food establishments recovered. Since then, potato prices in some markets have now reached INR 40 per kilogram (USD 0.54), with the average across major Indian markets at INR 33 per kilogram (USD 0.44), which is nearly double the average July price over the past ten years (Figure 2).

As the number of positive COVID-19 cases spikes again with the relaxation of the lockdown, high price fluctuations are expected as the state maneuver to contain the virus and likely to stay high until early rabi harvest December. However, it is possible that prices could rise even higher depending on the recovery from restaurants, fast food places, and other food service establishments.

Implications for farmers

High potato prices are a double-edge sword for farmers. If prices are higher immediately after harvest, farmers benefit, including those small-scale, marginal and cash-crunched farmers who sell their produce to cover their expenses. If prices increase a few months after the harvest, as in the current situation, then large farmers and traders who have potatoes in cold storage disproportionately benefit.

High table potato prices also translate into high seed prices for the next season, creating problems for cash-starved small-scale and marginal farmers. In the current scenario, fewer seeds (as much as 30% less than in previous years) have been placed in cold storage. Chastened by low seed prices in the past couple of seasons, many farmers were quick to sell seed potato right after the harvest to take advantage of the high market prices; while others continue to sell seed potato from cold storage as the prices have climbed higher in recent weeks. This trend will continue into the planting season as long as prices remain high.

The effects of high potato prices are reflected in current seed prices for the rabi planting season, which have reached INR 30‒35 per kilogram, excluding transportation. To put things in perspective, seed prices were INR 12‒14 per kilogram last season. The situation is so tight that some seed producers are not even willing to fix prices right now as they expect them to climb even as planting season approaches.

High potato prices will encourage farmers in the potato belt areas of India to expand cultivation in the coming season. However, those who invest in expensive seed and expand cultivation will not be guaranteed higher profit. Conventional wisdoms shows that high prices in one season typically generate higher production in the next season and, thus, lower prices. This dynamic could be especially true with a perishable commodity such as potato, which farmers cannot hold onto for long before incurring additional costs for cold storage. Therefore, prices tend to crash after a bumper harvest.

Knowing this, farmers can decrease their risk by planting early or opting for short-duration and early-maturing varieties that will enable them to sell their produce before the normal harvest floods the market. An early harvest by three weeks can result in 20‒30% higher prices. In certain locations in Punjab, Haryana and Uttar Pradesh, where the climate is suitable for farmers to plant in September and harvest in December, they can make high profits this year. Even January and February harvests are likely to bring in high prices for farmers.

Samarendu Mohanty, Asia Regional Director, International Potato Center