The need to innovate in agriculture is more urgent than ever. Rising populations will require 60% more food by 2050. Increasing urbanization in Africa and Asia and the impacts of climate change demand we produce this food with fewer inputs. While much of the world struggles with the threat of food insecurity, the cost of nutritious foods in the developing world far exceeds that paid in industrialized nations. At the same time, we are running out of time to achieve the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, as in many countries we are just nine harvests away from 2030.

But the term “innovation” is typically associated with the worlds of high-tech, electronics, architecture and design, not agriculture nor international development. What promise does innovation hold for agriculture? How can innovations be developed and sustained to maximize their value? And how can innovation help improve and transform the lives of smallholder farmers around the world?

To answer these questions and others, several experts from the CGIAR, investors, academia, and the private sector gathered online for an engaging, lively 90-minute discussion about the role of innovation to inspire and ignite changes to help the developing world achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Hosted by the International Potato Center (CIP), the speakers were invited to share their experiences with innovation for agriculture, including the lessons learned from previous field work with new crop varieties, agronomic practices, and mechanical improvements.

“Innovation is often taken for granted as part of the R&D process,” said Barbara Wells, the Director General for CIP, and recently named the Global Director for Genetic Innovation for the CGIAR. “Technologies that remain on the shelf are not innovation. We must measure our success by how our innovations improve the lives of smallholder farmers and vulnerable communities around the world.”

Indeed, all of the presenters said that without an agreed-upon understanding of the merits of innovation, achieving their goals would be more challenging.

“We know innovation when we see it but we don’t necessarily understand how to maximize its values,” said Marco Ferroni, the Chair of the CGIAR System Board. “The CGIAR is steeped in science and research but we need innovation to create improved expressions of welfare – nutrition, food security and incomes. This is how we create value for the people we serve, who are counting on us.”

For example, we have improved seed for farmers. And improved crop varieties with higher yields and more resilient traits. But if we don’t have a delivery system or available market for these varieties, then our work is for naught.”

While innovation is usually thought of in terms of success, Hugo Campos, the Director of Research at CIP, reminded the audience that failing is also important.

“Innovation is about having a ‘clever failure’ mindset so we can capitalize quickly on what we learn. New crop varieties take several years to produce, so we must quickly, cheaply fail and learn from our failings so that these varieties are developed to have impact,” he said.

Mindsets, and the need to change them, was a consistent theme throughout the webinar, as each presenter gave unique perspectives about nurturing innovations to have maximum and inclusive impact.

Hale Ann Tufan runs the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Crop Improvement at Cornell University. Her background as a plant scientist and gender researcher has shown her that when we think about end-users, not all end-users are the same.

“We need to reject the idea that agriculture and innovation are gender neutral and carefully consider whose lives we are improving. This idea [should be] at the heart of what innovation strive for. We know women have less access to productive resources… so we need to think critically about how we operationalize gender equality as a value for innovation.”

The webinar included five innovation “case studies” from research-for-development and private sector organizations to provide some examples of success in innovation – but also the value of their failings.

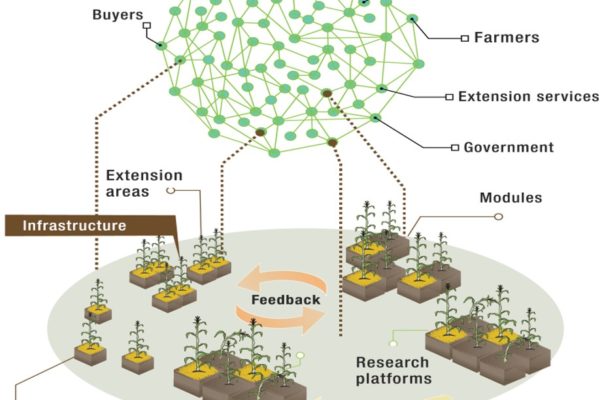

At the International Center for Maize and Wheat Improvement (CIMMYT), the Mas Agro program employs a holistic business model (figure 1) to help bridge innovation with traditional knowledge. Bram Govaerts, the Deputy Director for Research at CIMMYT, says inclusion for innovation must begin from the outset.

“How do you bring disparate actors together? You have conversations about what a better future looks like… Where are we today? Where do we want to be in the future? And then we build strategy around that vision.”

Perhaps the largest barrier to innovation for agriculture remains the issue of scaling – taking successful technologies and adapting them to the needs of larger populations.

On that topic, Graham Thiele, the Director of the CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas, gave an example of CIP’s very successful program with vitamin A-enriched orange-fleshed sweetpotato (OFSP), which has enabled nearly seven million households in Africa and Asia to enjoy this nutritious crop while learning how to grow and process the food for additional income (figure 2).

“The success of scaling OFSP required a package of interrelated innovations… We helped farmers improve their skill for cultivating vines for seed material and taught them how to use our Triple S technology to store healthy seed… We provided nutrition education to communities to inspire behavioral change, and we initiated business opportunities with OFSP puree products. To do this, we had to drill down and look at what our beneficiaries needed and wanted and why.”

The success of the OSFP innovation in Africa has enabled other humanitarian organizations to capitalize on this innovation. Lauren Landis with the World Food Programme in Kenya says they are “big fans” of OFSP to help meet their objectives with farmers living in dry climates. In the WFP’s target population, 26% of people have stunted growth and 70% have iron and vitamin A deficiencies, which could be remedied with OFSP.

Figure 2: The innovation package for orange-fleshed sweetpotato has enabled nearly seven million families to adopt this nutritious crop, adding valuable nutrients and income to their households.

Thanks to collaboration with CIP, Landis says the WFP is making serious inroads against these challenges. “We have had success with OFSP adoption by families who appreciate the improved income. We find that the children love the taste of OFSP, which is good for their health. Now we must shift our focus to improving the storage and processing. That infrastructure does not come out of thin air.”

At the Syngenta Foundation for Sustainable Agriculture, Vivienne Anthony, the Director of its Demand-Led Breeding Program, said they had produced many varieties for farmers that people did not adopt. Syngenta thought the problems related to seed systems, but they were wrong.

“We had to put farmers at the heart of everything we do. It sounds obvious but it wasn’t the way we were approaching innovation,” she said. This is consistent with Hugo’s remarks that to succeed in innovation, you must always begin from the beneficiary/customer/end user and work your way back to the technology, never in the other way around. Today, Syngenta uses product profiles that define who the innovation serves and then creates a technical plan to meet their needs.

Similarly at East West Seed, Mary Ann Sayoc, the company’s Public Affairs Lead, said their success relied on improving their focus on end-users and finding like-minded partners who could amplify impact.

“Initially, we were providing training on imported crops thinking farmers could add these to their portfolios. But they weren’t interested. So we turned to breeding locally-grown foods and complementing variety development with agronomic training. It changed things for us.”

With successful understanding of end-user needs, the investments will come, said Jonas Chianu, the Chief Agricultural Economist with the African Development Bank. As reaching the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 will rely heavily on successful development in Africa, Chianu underscored the need for proper innovation.

“We know that technology matters and should be accessible. That scale matters because we must move from pilot level to transformation. And we know that partnership and collaboration are key to scaling. To create the environment for scaling, we must have the proper policy to facilitate business development. So we must all be in the same room to discuss creating this infrastructure.”

More than 300 people attended the webinar, representing 60 countries from 160 organizations around the world, a very positive sign for building momentum behind the arrival of the One CGIAR, which is expected later this year at the 2021 Food Systems Summit, a key event for initiating global initiatives for food systems transformation.