The Guardians of the Potato: the future of potato biodiversity is in their hands

High up in the Peruvian Andes, at altitudes of over 12,500 feet, a group of dedicated farmers painstakingly preserve the biodiversity of potato landraces for humanity. In Central Peru, a group of these farmers known as the Association of Guardians of Potato Landraces of Central Peru (AGUAPAN for its acronym in Spanish) is committed to growing at least 50 varieties on their farms with some planting as many as 500— resulting in a rainbow-like harvest of potatoes in shades of purple, pink, red, blue, black, yellow, and white.

Climate change, globalization, and urbanization are putting increased pressure on the world’s food supply. Erratic weather patterns and an increase in pests and disease are affecting the global food supply at a time when the world population has surpassed 7.5 billion.

With more than 4,000 varieties of potato landraces spanning the Andes, the genetic potential of the tubers preserved by the Guardians could fuel new varieties required to meet the challenges of a hungry world.

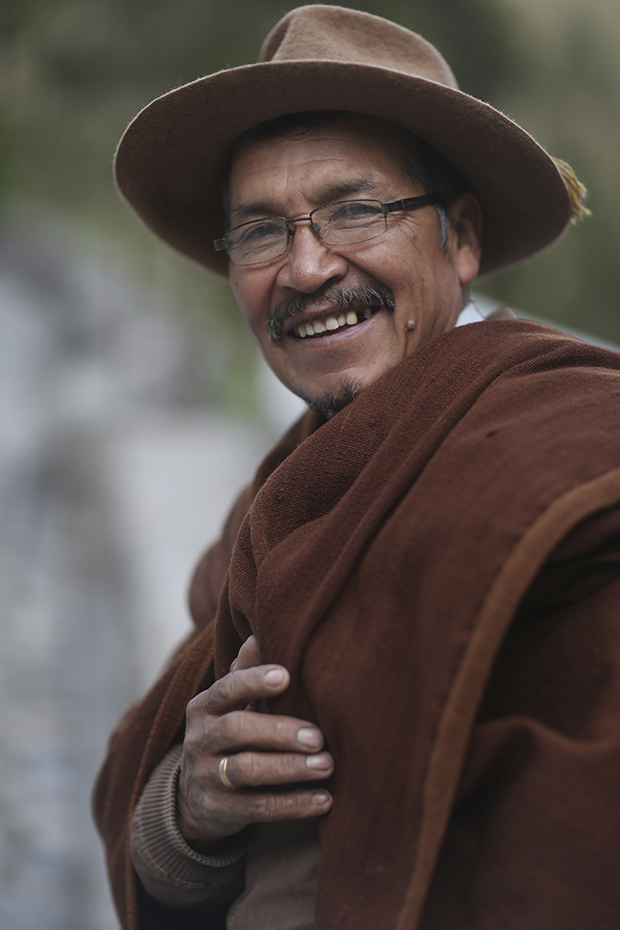

Members of AGUAPAN share their thoughts on what motivates them to cultivate native potato varieties.